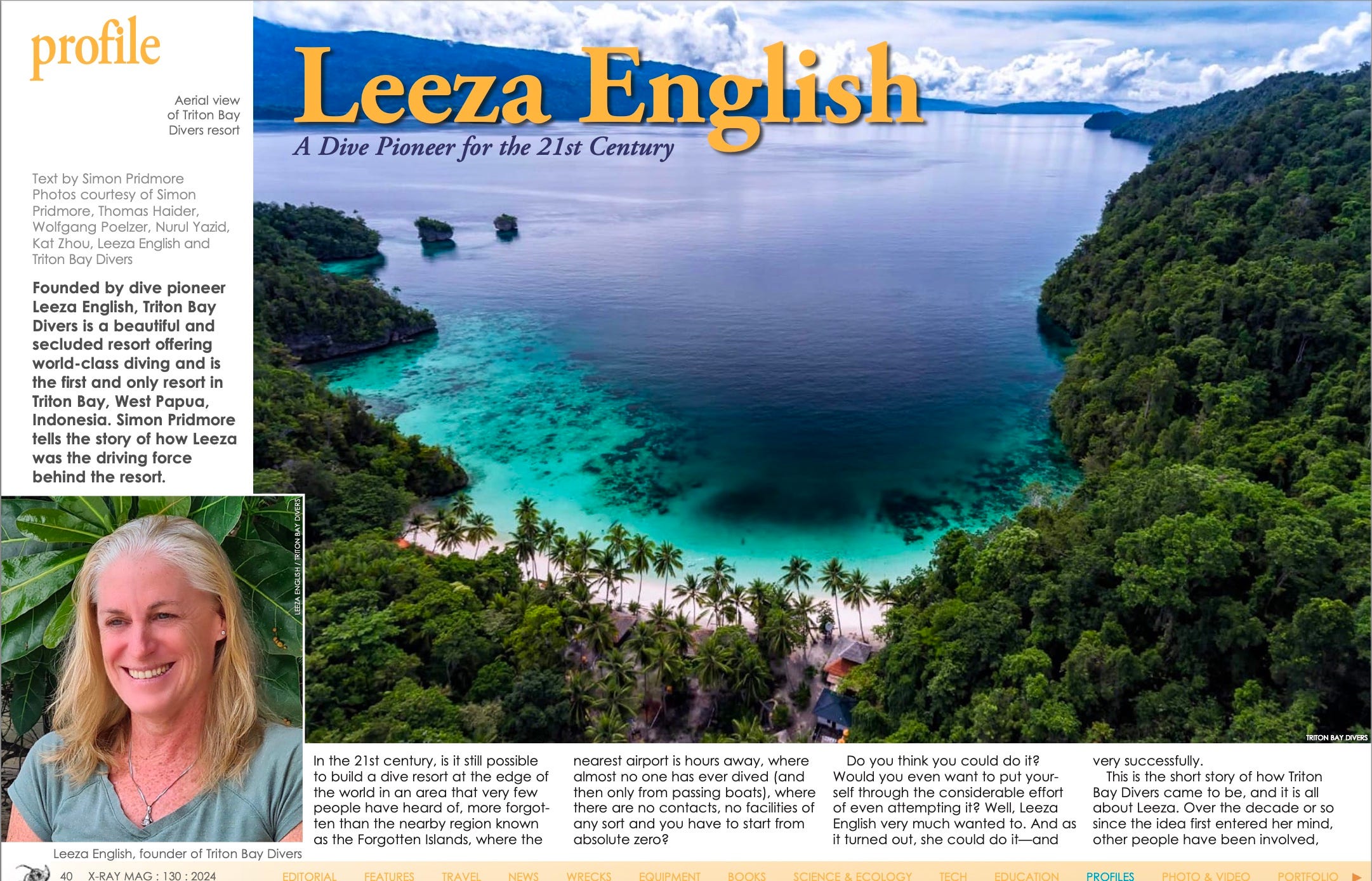

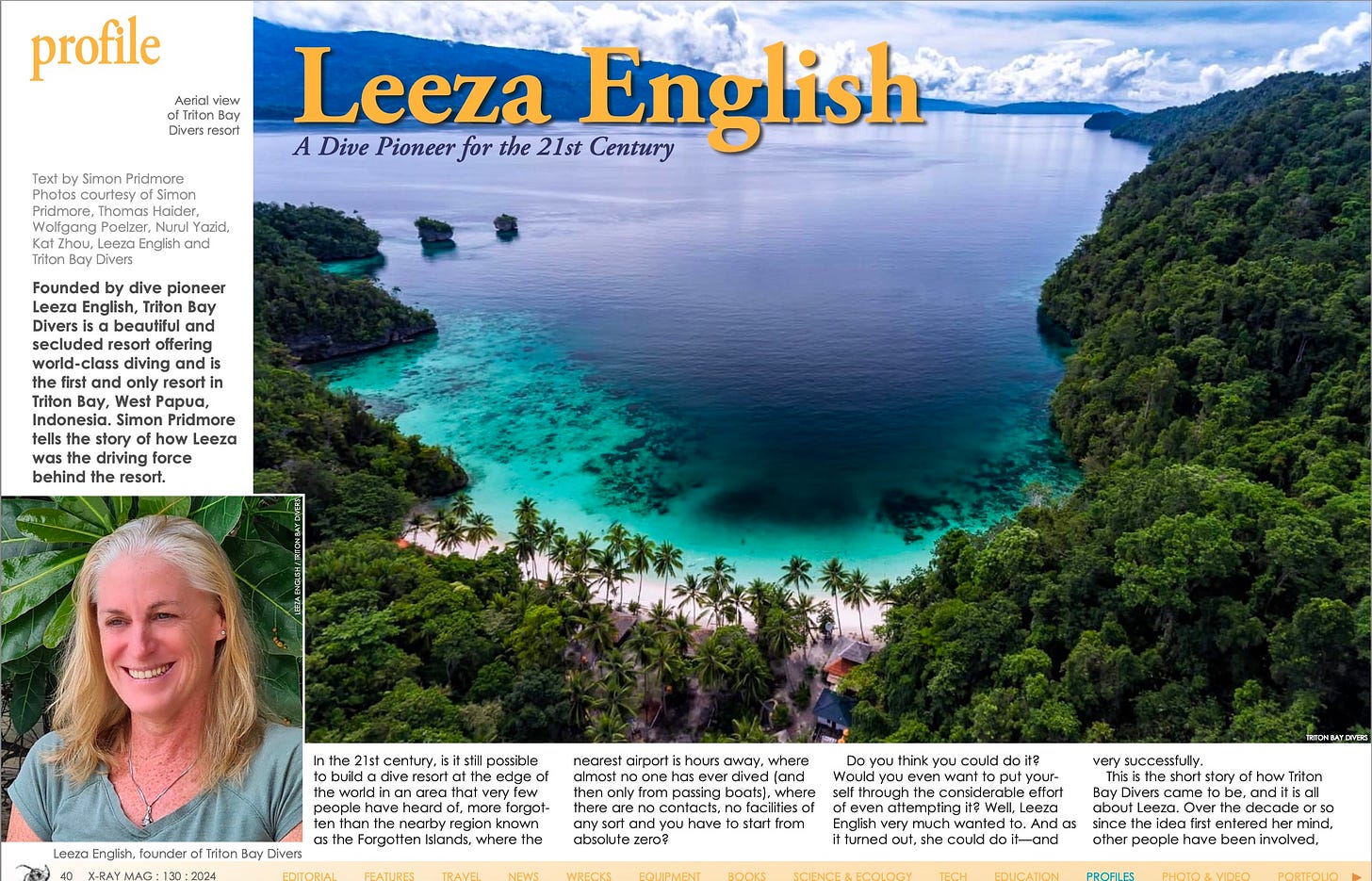

A Dive Pioneer for the 21st Century

When we first met Leeza and heard her story, I was struck by how similar her experience was to that of the people who first opened up now-world-famous areas such as Raja Ampat, Komodo and Lembeh in the 1980s and 1990s. Now, thirty, forty years on, she is fighting the same battles and dealing with the same issues as others had to overcome decades ago in more easily accessible parts of the vast Indonesian archipelago.

Her quest was similar to theirs - to discover a superb and hitherto-little-known marine environment, open up access to it for travelling divers and, simultaneously, find ways to protect the marine life and give people living in the area an opportunity to improve their livelihood, acquire new skills and receive a new source of income.

I felt Leeza’s story was well worth recording and sharing. Here’s a short clip.

The area ticked all her boxes, and there were no dive resorts within hundreds of kilometres. She realised she had an amazing opportunity here. You have one life, and you have to go with your gut.

She saw the adverse practical and logistical factors not as obstacles but as challenges. These could be handled later. The key was to find the right place. Everything else would follow. Given the will, all problems could be managed. Her instinct was, “If we build it, they will come.”

And she had a good feeling that this was the right place.

She and her business partner met with the West Papuan family that owned land right in the middle of the area with the best diving to finalise a deal. Their chosen location was in a secluded bay with a mountain behind it and a jungle down to the waterline. It faced the sunrise, which would mean beautiful mornings and cooler afternoons. There was also a source of fresh water.

They felt it would be best to incorporate the family into the business, as this might help things go more smoothly. Soon, the deal was done. By September 2014, the family had already cleared some of the land. Leeza returned on a ship with construction materials and fifteen workers, and they set up home in tents on the beach, with no toilet and a burner for pot noodles and tempeh, although the tempeh never lasted more than a couple of days. Then it was noodles, noodles, and more noodles until the next supply boat arrived. At first, the water pouring down the mountain was their shower, but after a few weeks of struggling across the rocks to bathe, they made life a little easier for themselves by running a water pipe from the waterfall to the beach.

To read more, you can click here for the text version of the article

Or, better, click here to download a PDF of the piece with pictures

And click here to download the whole magazine. It’s free of charge.

Here are a few images from the article

After visiting last year, with Sofie’s help, I wrote a short newsletter piece, as follows.

Remote but worth it…

The website tagline for Triton Bay Divers reads “remote, but worth it” and is the perfect description for one of the most distant and hard-to-get-to resorts on the planet. It’s the dive centre at the end of the universe.

To paraphrase Douglas Adam’s slogan

“If you’ve visited six impossible dive sites this week, why not round it off with…?”.

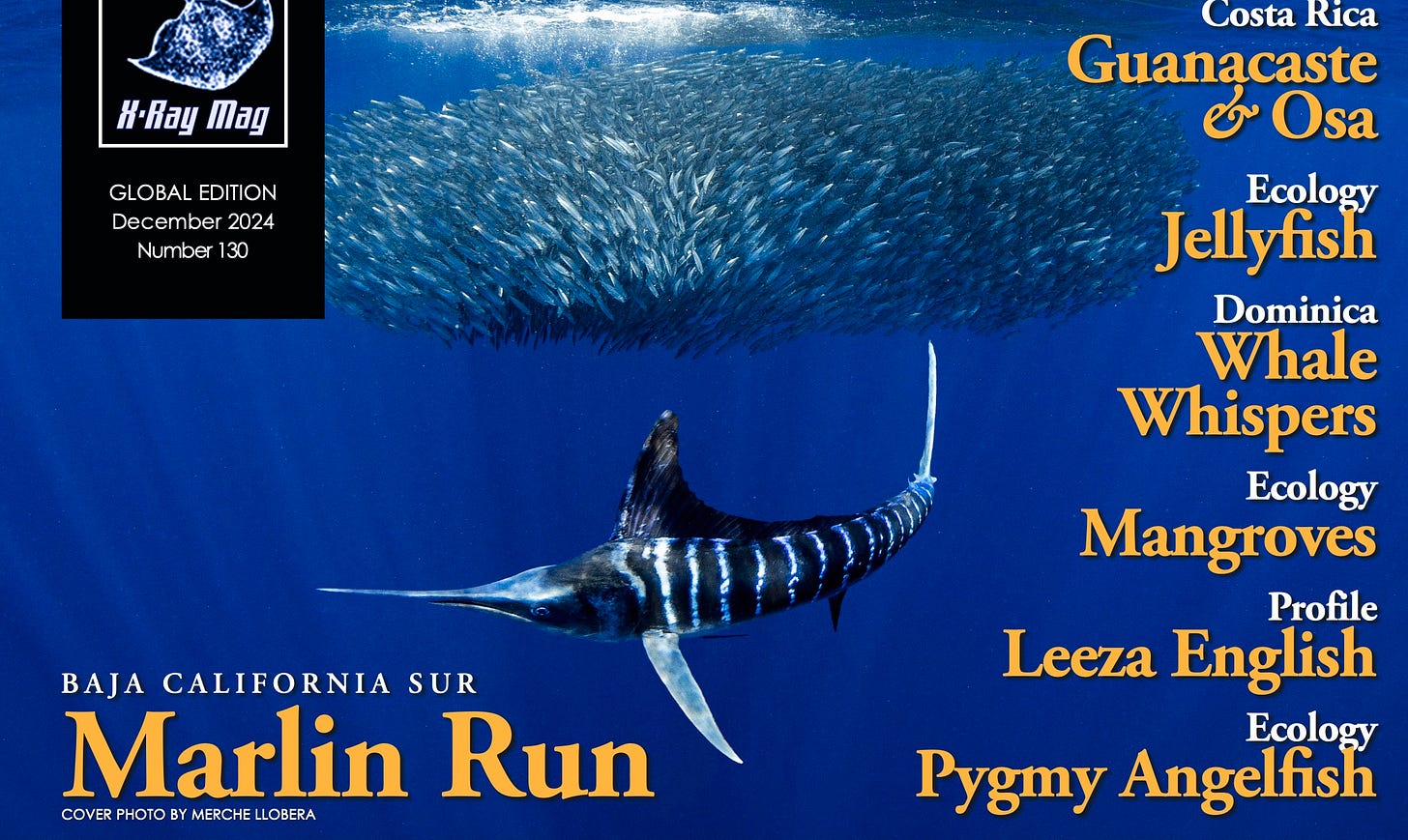

This is what Sofie wrote in her logbook, after one particularly astonishing dive.

Pintu Arus, Triton Bay - 24m, 60min, 28C/82F

Silversides all over the place, darkening the sun. Small tooth emperors stream across the bottom, like constant traffic, sometimes stopping at bommies, briefly changing to their mottled look - I don’t know why - then moving on again. I didn't have time to look and observe, there was too much going on.

A school of double-spotted queenfish arrived. I've never seen a school of them, only singles. Uwe loved them. By this point, I decide this is the best dive of my life. Then, roaming and foraging blue and golden trevally come past. All fish seem on steroids. Big groupers keep swimming past, so casually as if they were mere parrotfish. Meanwhile, the silversides are still swirling all around us.

Big hump head parrotfish and Napoleon swim casually by, munching coral as they go. The school of queenfish come swirling around us again.

The water is full of big surgeonfish, humpnose bigeye breams, and all kinds of sweet lips, including gold-striped and many-lined. The black coral is lush and probably full of marine life, such as longnose hawkfish, tozeuma shrimp, and maybe some ornate ghost pipefish, but I can't be bothered to look more closely. There is too much action to stop for small stuff.

We swim a bit further and stop. We just hang there and try to be part of the action. The silversides move in different shapes like the starlings over Brighton beach.

We can hear them changing direction. We wonder if something is chasing them and often there is, but we can't always see as our vision is blurred by fish. I see dive guide Jack pointing at something, I have no idea what it is as, again, I can't see past the swarm. It's noisy in the water, with lots of crackling and whooshing.

Suddenly I see stuff coming towards me. It's a school of jacks, I mean all kinds of jacks, big-eye, almaco, golden, blue ... everything on steroids again. Oh, and the GTs! There are a couple of GTs the size of Jack in there. I know because one came straight for him and stared him down. The sea is so full of action and so full of fish, there seem to be more fish than water. I hardly breathe. The fish come so close, I don't want them to move away. Eventually, they do. They leave as suddenly as they came. There is a cloud of spawn near the bottom and the seabed is covered with little wrasse feeding on it. I don't know what spawned, maybe fish, maybe sponges. I didn't see. I look back up and there's a group of about 20 mobulas. I scream through my regulator, I want everyone to see. But there is too much to look at, not everyone gets the chance to see them. Jack goes between conducting the fish orchestra and banging his tank with his pointer and telling us where to look. He tells me to look behind me. A school of fat barracuda appears. I've seen so many amazing things by now, a school of pickhandle barracuda feels so trivial.

We start swimming back to where we came from and see everything again in reverse. All the breams, sweetlips, streaming emperors. The queenfish make another appearance. Jack goes off to a sandy patch to see if he can find a wobbegong to show us. I can't say I am particularly interested. There is a time and a place for everything and a wobbegong sighting feels a bit too docile for this particular dive.

I'm so excited, my head feels like it's going to explode!

Part of me wishes I had a camera so I could show you what I saw. But part of me thinks I wouldn't have seen everything I saw had I had a camera between my face and the action.

(Our friend Sue did have a camera and she shot a few seconds of Sofie hanging, mesmerised in the water at 24m, as the jacks came swooping past, see below.)

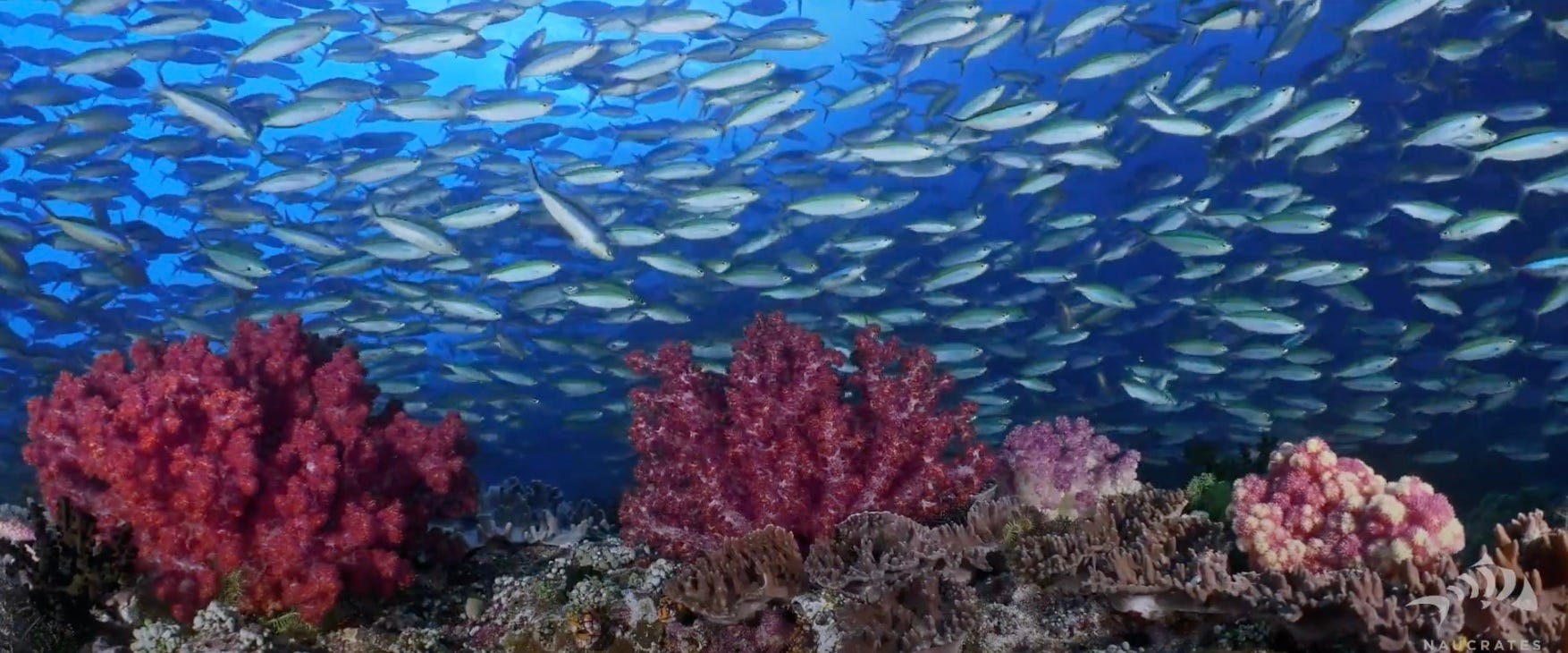

Here are a few other shots of Triton Bay Divers. It’s a beautiful location.

We will be back at Triton Bay Divers not once but for two separate visits in March 2025, and this time, Sofie has a camera…

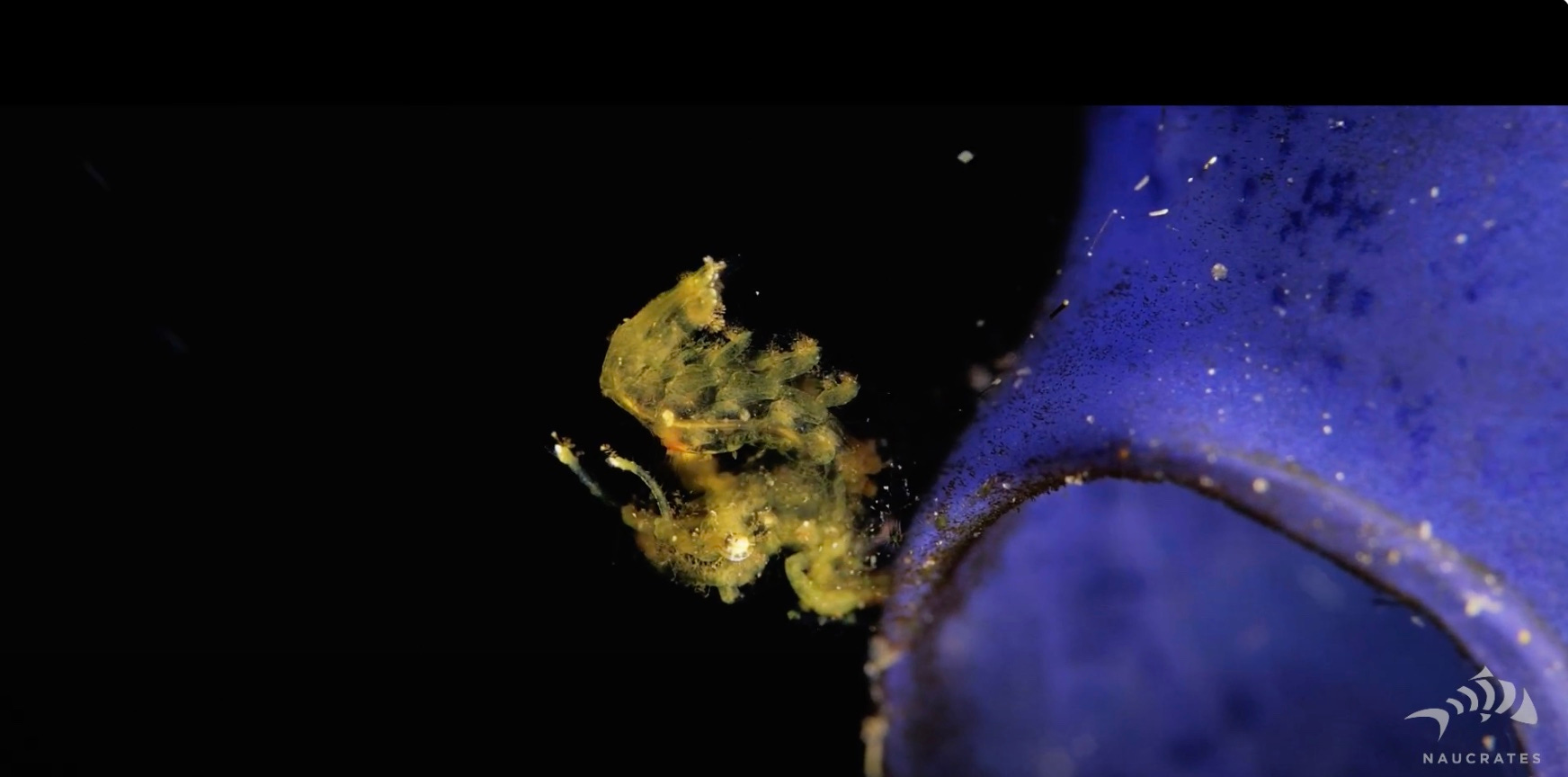

In the meantime, enjoy this video by Naucrates Underwater Videography

Click any of these stills to be taken straight to YouTube for 5 minutes in paradise.

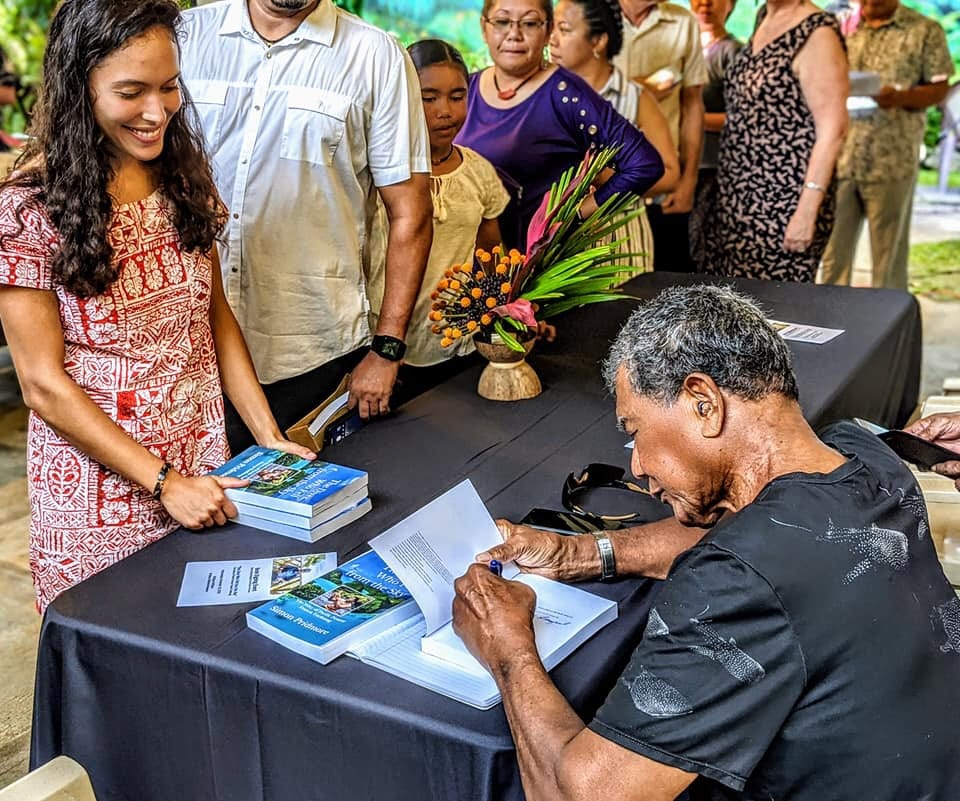

The Diver Who Fell from the Sky

In Leeza’s case, I especially enjoyed writing about a pioneer who is still on her journey, but back in 2019, I found myself looking back on the life of one of the very first scuba diving pioneers in the Pacific, Francis Toribiong, who discovered world-famous sites like Blue Corner and Ngemelis Wall and put his homeland of Palau on the scuba diving map.

We visited Palau for a while that year, spent time with Francis and photographer Tim Rock on land and sea, interviewed Francis’s family and friends, explored the islands and reefs and then produced a biography called The Diver Who Fell from the Sky, which recounts Francis’s extraordinary life and the equally extraordinary history of Palau during his lifetime.

The Diver Who Fell from the Sky on Amazon

Here’s my preface -

Maverick, innovator, entrepreneur, environmentalist and sheer force of nature, Francis Toribiong would have been a unique and significant individual no matter where in the world he was born. As it turned out, he was born in the islands of Palau in the Western Pacific at just the right time to apply his special set of skills and attributes to the task of helping his country find its place in the world.

Over a period of around 20 years at the end of the last century, he arguably did more than anyone to build Palau’s economy and help it develop into an independent, forward-looking nation.

Improbably, he achieved this via the sport of scuba diving.

Francis is a Pacific Islander like no other. He is the father of Palau tourism, a scuba diving pioneer, and an effective, tireless ambassador for both his country and its abundant marine and land resources.

He was born poor and had no academic leanings. Yet he was driven to succeed by a combination of duty, faith, a deep-seated determination to do the right thing and an absolute refusal ever to compromise his values.

For his whole life, he has been a devoted friend to strangers and an implacable opponent to anybody who, through malevolence or negligence, threatens Palau’s considerable natural treasures. He has also been the perfect host to generations of scuba divers from all over the world, who have visited Palau to see those treasures for themselves.

And, as well as all that, he was Palau’s first-ever skydiver and jump master – known by people throughout the islands as the Palauan who fell from the sky.

They were speaking both literally and figuratively. He was so completely different from all of his contemporaries in terms of his demeanor, his ambitions and his vision, that it was as if he had come from outer space. Palau has seen nobody else quite like him during his lifetime and there was no historical precedent for what Francis Toribiong did. He had no operations manual to consult and no examples to follow. He wrote his own life story.

Francis Toribiong was the first Palauan ever to seek and seize the international narrative. No Palauan in history, in any context or field, had ever thought to go out into the world and say:

“This is Palau – what we have is wonderful. Come and see!”

It is impossible to tell this story without also telling the recent story of Palau and its people: the events that informed the times into which Francis was born and the changes that occurred during his lifetime, both those wrought by him and other developments that just carried him and his countrymen along. But the intention here was never to write a political treatise, just to recount the story of an extraordinary Pacific life.

The Diver Who Fell from the Sky on Amazon

The Andrea Doria’s Haunting Call

Scuba diving stories in subject-dedicated media are common, of course, but breaking through the barrier and getting the mass-market media to focus on diving-related topics is a much rarer achievement.

As I discuss in my Technically Speaking book/audiobook on the history of technical diving, one of the catalysts that launched the sport was an article in the June 19, 1989 issue of Sports Illustrated written by deep wreck diver Cathie Cush about divers dicing with death on deep wreck dives.

Scuba diving’s evolution from a dangerous activity engaged in by daring elite explorers and TV action heroes to a moderately exciting pastime that all the family could enjoy may have created a whole new leisure industry, but it had also reduced the sport’s newsworthiness.

At that time, Sports Illustrated rarely published scuba diving stories. It focused on competitive sports and only ran pieces on adventure sports when something exotic, thrilling or new was going on.

Cush’s article checked all those boxes. It was entitled “The Andrea Doria’s Haunting Call” and it gave the subscribers to America’s most widely read sports magazine a glimpse of a diving world that most readers, even the divers among them, had no idea existed.

Here’s an excerpt.

“I tried to put all this out of my mind the next day as my diving partner, Ed Soellner, and I pulled ourselves down the anchor line into the pea-green ocean to the Andrea Doria. When we reached the hull, Soellner disappeared into the hole that Gimbel had cut in the ship's side in 1981 to retrieve the safe. The hole, at about 220 feet, provides access to the first-class dining area, where divers dig for china and crystal bearing the Italian Line's crest. Just a few feet away from where Soellner was digging, another diver died, in 1985, when he was caught in heavy cables. I confined my sight-seeing to the hull and the promenade deck.

After 20 minutes I had to begin the long decompression necessary to avoid the bends. There was no sign of Soellner, and no time to look for him. I started up the anchor line, my heart pounding. I decompressed for nearly an hour, hanging on to the anchor rope with both hands in a current so strong that it threatened to rip my mask away if I turned my head to the side. Hanging is tiring, cold and, once you've seen the first four dozen jellyfish float by, boring. But if your partner is missing, there is plenty of time for anxiety to build. I was sure Soellner was all right...but what if he wasn't? Finally, as I neared the surface, I made out his silhouette 30 to 40 feet beneath my fins.”

It’s breathtaking writing and the article was enormously influential. Even most of the divers among Sports Illustrated’s readership had no idea that people were doing dives like this for sport.

Now they did.

Technically Speaking on Amazon and Audible

The Canoe Whisperer

Recently, Tamara Thomsen’s extraordinary work finding and recovering ancient native American canoes in the Great Lakes has seized the imagination of the wider non-diving world.

The Smithsonian recently ran a long article putting the work into context.

Smithsonian Magazine - January/February 2025

Here’s what they had to say

Tamara Thomsen was 24 feet underwater when she spotted it: the decaying end of a dugout canoe, a great white oak carved some 1,200 years ago. It was jutting out of a sandy ridge in Wisconsin’s Lake Mendota—a body of water skirting Madison, the state capital—and she knew it was a remarkable find. “What I did not understand was the breadth of the discovery.”

Thomsen was diving that summer day in 2021 as a private citizen, chasing fish and collecting trash. More often, you’ll find the maritime archaeologist in the Great Lakes, surveying deep-water sites for the Wisconsin Historical Society. Lake Mendota had not been on the archaeologist’s radar, and she certainly wasn’t hunting for dugout canoes. Thomsen usually looks for shipwrecks, like 19th-century freighters.

It might seem remarkable that she recognized the find for what it was: Dugout canoes, the world’s oldest boat type found to date, are simply hollowed-out logs. In 2018, however, Thomsen had teamed up with Sissel Schroeder, an archaeologist with the University of Wisconsin-Madison, to help an undergraduate student catalog Wisconsin’s extant dugout canoes. When the project began, historians believed 11 existed in collections across the state. Less than a year later, after scouring private collections, supper clubs, local museums and more, the team had counted 34.

Thomsen’s 2021 find spurred the two women to continue their hunt—and take it public. Establishing the Wisconsin Dugout Canoe Survey Project, the pair and helpers have so far documented a full 79 dugout canoes, including two of the ten oldest dugouts found in eastern North America, ranging between 4,000 and 5,000 years old. Wisconsin’s dugout catalog sheds light on Indigenous knowledge, habits of trade and travel—and even environmental adaptation.

In fact, a map of the found dugouts shows us not just where this community lived, but how it moved and changed in pace with the Earth over millennia: Just 300 yards from where Thomsen found that first canoe in Mendota, she later uncovered a cache of at least ten canoes along an underwater ridge that geologists have identified as a previous, now-lost shoreline, a beach in the savannas of ancient Dejope.

“No one does this,” says Wisconsin state archaeologist Amy Rosebrough, referring to the relatively new approach of treating small, urban waterways as potential archaeological sites. “The only thing even comparable that I can think of is the mudskippers in London who walk up and down the Thames.”

Like those mudskippers, also known as mudlarks, who scour riverbanks for artifacts from London’s past—Roman pottery, Victorian silverware—everyday citizens report dugout sightings across Wisconsin. The best specimens have wound up at historical societies and museums, including a Menominee canoe currently sitting in Smithsonian Institution storage in Maryland. Some are hung high above supper club tables or auctioned off to private collectors. A few, miraculously, have managed to stay within their tribes, including the Ho-Chunk, the Menominee and the Lac du Flambeau.

It’s the rumors of still-submerged specimens—mostly anecdotes from hunters, fishers and boaters—that make Thomsen and Schroeder put in serious legwork. Receiving leads via a tipline, the women then go hunting themselves, diving, wading or kayaking in Wisconsin’s bogs and shallow lakes, with little more to guide them than loose coordinates and a snorkel.

The duo has thus far confirmed 79 of 112 reports across the state, and new ones are still popping up with regularity. Most of the finds are in surprisingly good condition—a few have even been accompanied by paddles or tools, like net sinkers and an adz, a wood-cutting implement similar to an ax. Some have turned out to be fragments, which is even more remarkable: The worse the specimen, the more likely it’s deemed kindling and thrown on the fire.

When they locate a dugout, Thomsen and Schroeder start by collecting data the old-fashioned way. They fill notebooks with drawings, measurements and lists of stylistic quirks, from thwarts (structural crosspieces) and drag marks to charring and paint. Leaving all specimens in situ, Thomsen then does photogrammetry using a GoPro camera; when working above ground, she also uses lidar, or “light detection and ranging,” a remote measuring sensor built into newer iPhones and iPads that, with a 3D scanning app, can create an instant 3D model for further study. “Sometimes the GoPro works, and sometimes the lidar works,” says Thomsen. “Sometimes they’re possessed by spirits, and they don’t want to be scanned at all.”

When possible, the duo also takes a sample of wood about the size of a matchstick—typically from the outer part of the canoe—for further analysis and dating. Ranging in age from 150 to nearly 5,000 years, varying in length from 7 to 36 feet, many canoes postdate the arrival of Europeans. Once in a while, though, they’ll find a specimen that shares a timeline with Beowulf, the Phoenician alphabet or even early math.

Thomsen has made discoveries at Lake Mendota that stand as some of the state’s oldest: Carbon dating places her first find at 1.200 years old and her second around 3,000 years old. The Mendota cache currently includes the survey’s oldest, an elm dugout carbon-dated at more than 4,500 years old.

And there’s more. I highly recommend you read the full article.

Nanhai #1

Reading news of ancient shipwrecks is often how non-divers become aware of our world.

Most people in the UK are aware of the Mary Rose Museum in Portsmouth Historic Dockyard, built around the wreck of the 16th-century ship raised in 1982.

More than 500 British Sub Aqua Club (BSAC) divers were involved in the excavation, which took place over three years and the event raised the profile of scuba diving throughout the country.

On the other side of the globe, in 1987, in the South China Sea, divers from a British company working with the Guangzhou Salvage Bureau found a shipwreck that was even older and equally inspirational.

It dates from the Song Dynasty (960 to 1279 AD) and was laden with porcelain. Like the Mary Rose, it is a time capsule of its era and again like the Mary Rose, it has been salvaged in its entirety and has a museum built around it.

This is the Maritime Silk Road Museum of Guangdong in Yangjiang

The UNESCO website has an excellent summary.

The wreck of the Nanhai No 1 was found in the western part of the mouth of the Pearl River (Zhu Jiang), the starting point of China’s “Maritime Silk Road”, which once connected China with the Middle East and Europe. It takes its name from 'Nanhai' - the South China Sea. The wreck is in exceptional condition. It is thought to contain 60,000 to 80,000 precious pieces of cargo, especially ceramics.

The wreck is currently still entirely covered by silt and its location and shape had to be verified by a sub-bottom profiler. It was recovered in an exceptional exploit. A bottomless steel container was placed over the wreck site. The lower part of the container was sharpened and it was driven into the seabed by placing heavy concrete weights on the container. The surrounding area was then dug out, the container closed from below with steel sheets and the whole ship was raised.

The museum is at Hailing Island close to Yangjiang, a three-hour drive from Guangzhou. The museum features an aquarium with the same water quality, temperature and environment as the spot in which the wreck was discovered. Archaeologists will now excavate the vessel inside the aquarium, thereby enabling visitors to observe underwater archaeological work in a museum environment.

The remains of the ancient vessel are expected to yield critical information on ancient Chinese shipbuilding and navigation technologies. Its significance has been compared to the famous terracotta warriors discovered in Xian.

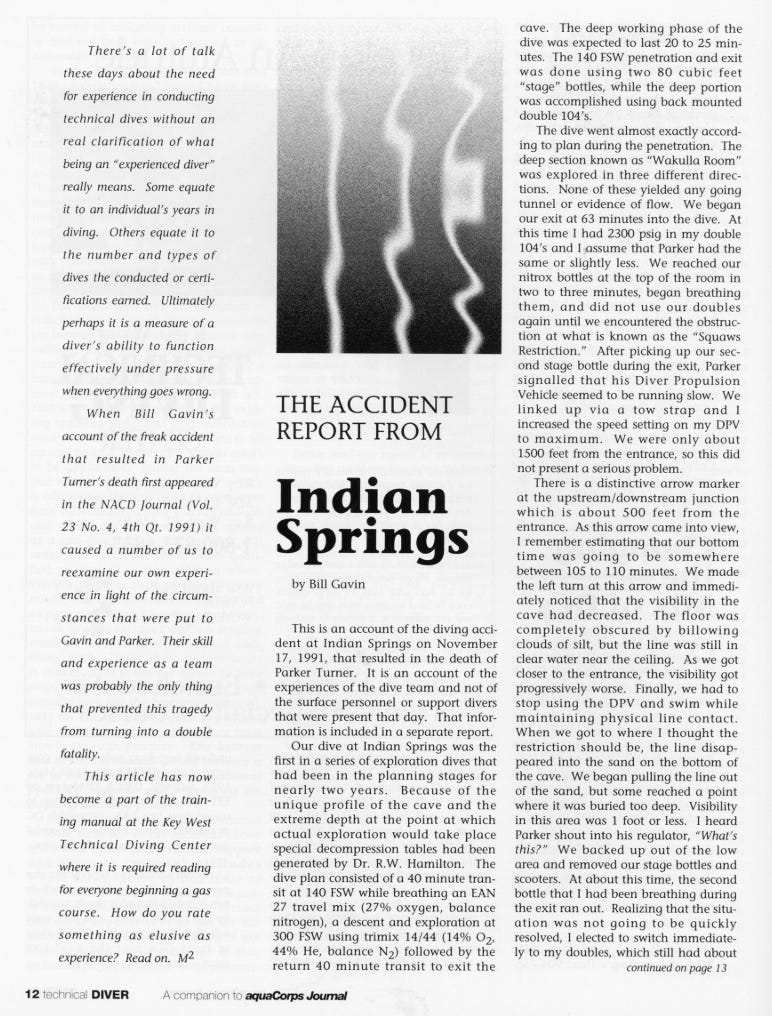

The Indian Springs Accident

These days, we have much more access to information than we did in the past, and, fortunately, this information is not only contemporary. For instance, when writing Technically Speaking, I was able to do my research consulting magazines, newsletters and conference minutes dating from a period long before the Internet, mainly because generous souls saw fit to upload them

One of these generous souls is Michael Menduno, formerly owner and editor of aquaCORPS magazine and now running InDepth. When I was writing my book in 2021/2022, searching online, looking through my files and conducting interviews, I was frustrated that I couldn’t find an important accident report from 1991 that had an enormous influence on our development as technical divers in the early 1990s.

This report was written by Bill Gavin for the National Association of Cave Divers (NACD) in the USA and it concerned the death of one of US cave diving’s greats - Parker Turner - and the survival of Turner’s dive buddy that day, Gavin himself. I knew it existed, I remembered discussing it with Billy Deans when he passed through Guam towards the end of the 1990s and thought it was in an issue of aquaCORPS, but I couldn’t find it.

Then, recently, InDepth featured the report and republished it. It turns out that it had appeared in one of the occasional Technical Diver newsletters that aquaCORPS would put out.

Anyway, I now have it. And it’s now available to everyone right here.

The Accident Report from Indian Springs by Bill Gavin

I warn you, it makes for heart-in-the-mouth reading, but you won’t forget it and that’s what you want writing to be - unforgettable. That’s why media exists.

Click on the image to link to the full document, which runs to three pages. If you encounter any difficulties, email me and tell me about it.

Last, but not least

As I write, Chinese New Year is almost upon us, families are gathering, homes are being tidied up, decorations are in preparation, the nearby corner shop is doing a booming business in firecrackers, the Year of the Dragon is almost done and dusted and we are about to enter the Year of the Snake.

So although this is a wood snake year, not a water snake year, nevertheless I thought I’d leave you with some of Kyo Liu’s images taken while we were working on the Dive into Taiwan book around Taiwan’s Orchid Island, where several species of sea snake abound.

See You Next Time

That’s all for this issue of Scuba Conversational. I hope you enjoyed it.

Sofie and I wish you all the best for the Year of the Snake

See you again soon in Scuba Conversational Issue #69.

Safe diving!

Live your articles, Simon. Also, as a PR guy, I can relate to trying to get scuba in mass media. It is no easy task!