Deep Beginnings

I am currently working on the second volume in my Technically Speaking series of books - subtitled Strategies - and recently drafted a chapter called “Paradigms for Deep Diving”.

Part of my lead-in reads:

So, the deeper you go, you have a scenario where the diver can be:

• 1. Finding it more difficult to breathe,

• 2. Retaining more and more CO2 in their bloodstream,

• 3. At increasing risk of an oxygen-induced convulsion and

• 4. On the verge of panic.

Deep, mixed-gas sport diving is the main thing that separates our current scuba era from preceding eras. In the past, it was banned, rejected, vilified, pushed to the sidelines and not to be spoken of or written about.

And for good reason - deep diving killed divers, and this was bad for the sport’s reputation, threatened its growth and introduced the prospect of government control and regulation.

Emergence

In my first book in the Technically Speaking series, I tell the story of how deep, mixed gas sport diving - later to become known as technical diving - became an integral part of the sport

This is an extract from Chapter 3, Emergence.

“In 1989, three separate things combined to bring extreme sport diving out of the shadows.

First, writer and deep wreck diver Cathie Cush pitched an article to Sports Illustrated about divers dicing with death on deep wreck dives. The magazine liked it and ran it in its June 19, 1989, issue.

Scuba diving’s evolution from a dangerous activity engaged in by daring elite explorers and TV action heroes to a moderately exciting pastime that all the family could enjoy may have created a whole new leisure industry. However, it also reduced the sport’s newsworthiness.

At that time, Sports Illustrated rarely published scuba diving stories. It focused on competitive sports and only ran pieces on adventure sports when something exotic, thrilling or new was going on.

Cush’s article checked all those boxes. It was entitled “The Andrea Doria’s Haunting Call” and it gave the subscribers to America’s most widely read sports magazine a glimpse of a diving world that most readers, even the divers among them, had no idea existed. She wrote:

“I tried to put all this out of my mind the next day as my diving partner, Ed Soellner, and I pulled ourselves down the anchor line into the pea-green ocean to the Andrea Doria. When we reached the hull, Soellner disappeared into the hole that Gimbel had cut in the ship's side in 1981 to retrieve the safe. The hole, at about 220 feet, provides access to the first-class dining area, where divers dig for china and crystal bearing the Italian Line's crest. Just a few feet away from where Soellner was digging, another diver died, in 1985, when he was caught in heavy cables. I confined my sight-seeing to the hull and the promenade deck.

After 20 minutes I had to begin the long decompression necessary to avoid the bends. There was no sign of Soellner and no time to look for him. I started up the anchor line, my heart pounding. I decompressed for nearly an hour, hanging on to the anchor rope with both hands in a current so strong that it threatened to rip my mask away if I turned my head to the side. Hanging is tiring, cold and, once you've seen the first four dozen jellyfish float by, boring. But if your partner is missing, there is plenty of time for anxiety to build. I was sure Soellner was all right...but what if he wasn't? Finally, as I neared the surface, I made out his silhouette 30 to 40 feet beneath my fins.”

It’s breathtaking stuff. Cush had not even bothered to pitch the article to the mainstream diving media. She knew none of them would even consider running it. Dead divers - 220ft - decompression - it was about as far off-message for those magazines and their readers as you could get.

But Sports Illustrated loved it!

The second development came in October 1989, when wreck diving pioneer Gary Gentile finally won a five-year court battle to force NOAA to allow him and his team to dive the wreck of the USS Monitor ironclad that lay in depths far beyond normal sport diving depths and in murky, fast-moving waters.

These circumstances described the sort of dives Gentile and others like him had been doing routinely and safely for many years. Yet, NOAA, which was responsible for supervising the shipwreck site - a national monument - claimed the dive was too dangerous for sport divers and denied him permission.

In the explanatory judgement issued following Gentile’s victory, the judge wrote:

“The activities of Mr Gentile and his witnesses such as Messrs Watts, Deans and Bielenda lie in the penumbral area between sport and commercial divers due to the increased depth as well as the profit and business aspects of their activities…The appellant and other staged decompression divers are not sport or novice divers. Their training, experience and certifications reflect a substantially greater proficiency.”

This represented the first official acceptance that deep, planned decompression diving was a valid and viable sports activity nestled somewhere between sport and professional diving and not something that could or should be prohibited.

Third, also in October 1989, Californian writer, deep diver, and technology geek, Michael Menduno started writing articles for the first issue of a magazine that he hoped would act as a forum and information exchange portal for the sport diving world beyond the mainstream. He saw what was happening as a technological revolution akin to the one he had previously seen in the computer world.

The magazine was aquaCORPS: The Journal for Experienced Divers and Menduno launched it at the Orlando Florida DEMA Show in January 1990. It was a 36-page, black and white, saddle-stitched, booklet with no advertisements and a 2500-copy print run. Menduno remembers senior figures in the diving world passing by his booth, picking up a copy, leafing through it and then walking away.

Afterwards, some of them called him and eventually became staunch supporters. Billy Deans of Key West Diver was one and commercial diving, mixed gas diving and diving safety pioneer Lad Handelman, the CEO of Oceaneering Inc. was another. But others left the aquaCORPS booth shaking their heads. They would later try to make the magazine and everything it represented disappear.

Due in great part to the efforts of Cush, Gentile and Menduno, by early 1990, the rabbit of extreme sport diving was emerging, blinking into the light, out of the darkness of its hat.”

(Technically Speaking: Talks on Technical Diving Volume 1 Genesis and Exodus)

The secret to safe deep diving lay in a system of procedures established over several years in the 1980s and 1990s, mainly by cave and wreck divers, and the magic ingredient was adding helium to oxygen and nitrogen to create a breathing gas we named trimix.

On www.simonpridmore.com, I have a short blog called Scuba Solutions, which answers common questions that divers have.

One of these is:

What is trimix and why do divers use it?

The short answer I give runs as follows.

In the early 1990s, deep sport divers were let into a secret that enabled them to carry out deep dives with a clear head, reduced risk and a light, easily breathable gas in their lungs.

That secret was trimix, a mixture of three gases, oxygen, nitrogen, and helium. Helium is a very light, non-toxic, minimally narcotic gas. Adding it to their breathing gas enables divers to reduce the percentage of oxygen and thus reduce the risk of oxygen toxicity that is always present when you dive below 200ft (60m) or so using air. Trimix is easier to breathe, as it is less dense than air. It is also much less narcotic.

There are two disadvantages to using helium. First, it is expensive. Second, at high partial pressures, it has unwanted effects on the diver’s central nervous system.

Commercial diving and military operations have known for a long time that using helium has huge physiological advantages for a diver working at depth, although, rather than trimix, the breathing gas of choice for professional deep divers is a mixture of oxygen and helium only, known as heliox.

They use no nitrogen at all and very high percentages of helium because their primary concern is to minimize narcosis in the working diver and the consideration of cost is secondary to getting the job done. Also, as they are in constant communication, divers and their surface supervisor can work together to manage any nervous system problems.

Sport divers are not so fortunate. We do not have the luxury of vast funds nor do we dive with a surface supervisor. But, then again, when we dive, we are usually just sightseeing and are not engaged in work that requires intense concentration. So deep sport divers tend to add only as much helium as they need to keep the amount of oxygen in their breathing mix within safe limits and maintain a manageable level of narcosis. It is also thought that a little nitrogen in the mix tends to offset nervous system issues.

Successful trimix diving involves far more than just changing the gas in the cylinders and plunging in. While the rewards of going to depths hitherto beyond the range of sport divers are substantial, this is not a level of diving to be taken lightly. You need to be prepared for longer decompression times, carefully controlled ascents and total dependence on decompression gases. Good training, self-discipline, attention to detail and a great deal of in-water experience are essential to success in trimix diving.

In this issue of Scuba Conversational, I describe some of the astonishing things that people have been doing and discovering all the way down there.

A Living Dinosaur

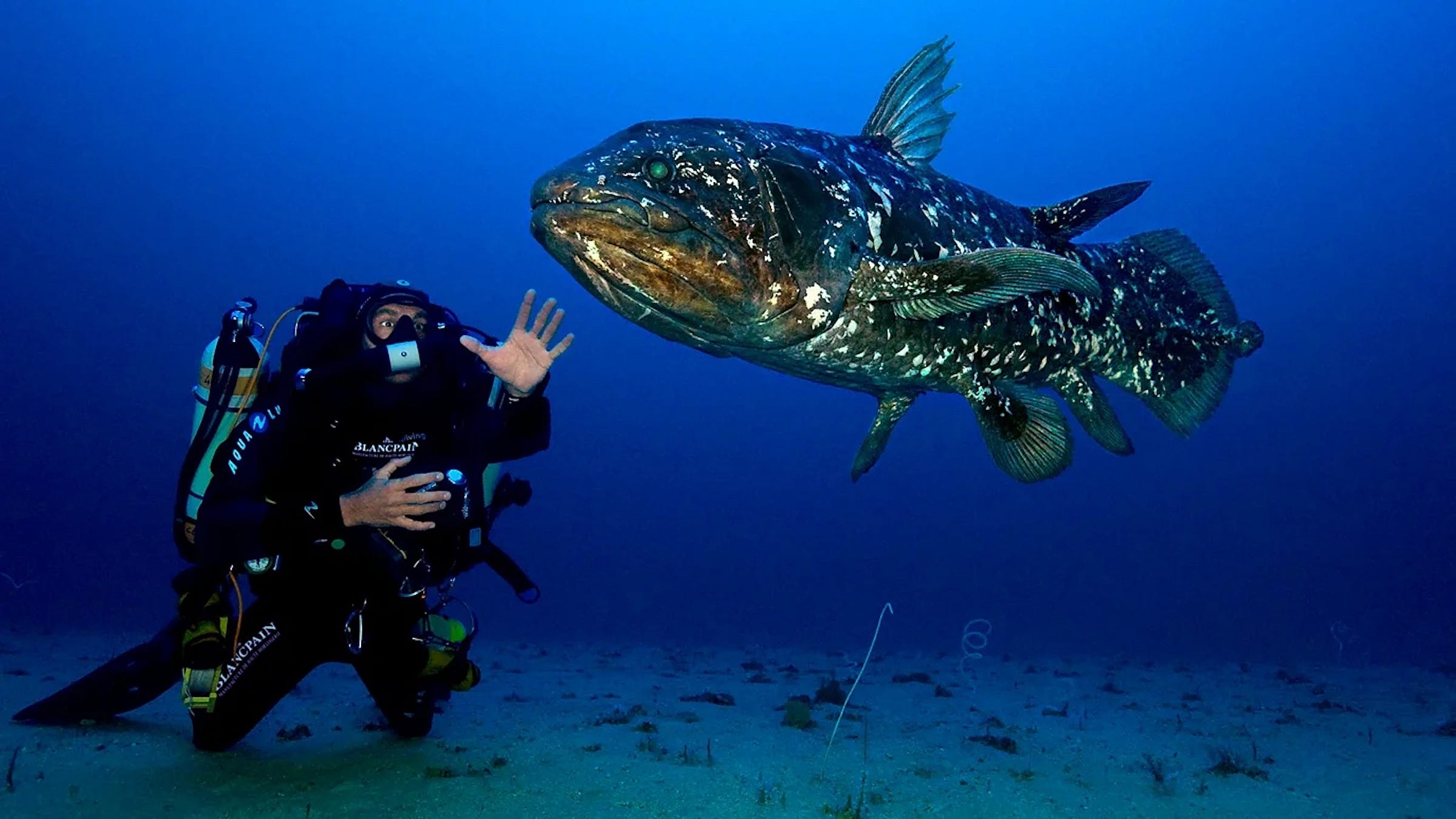

In 2010 four friends sank beneath the waves of Sodwana Bay, off the east coast of South Africa, where photographer, Laurent Ballesta stared directly into the eyes of a creature once thought to have died out with the dinosaurs – making him the first diver to photograph a living coelacanth.

"It's not just a fish we thought was extinct," says Ballesta. "It's a masterpiece in the history of evolution."

Venture back to the beginning of the age of the dinosaurs, and you'd find coelacanths in abundance, on every continent, living in the steamy marshes of the Triassic Period. Dating back 410 million years, the coelacanth belongs to the group of "lobe-finned" fish that left the ocean between about 390 and 360 million years ago. Its strong, fleshy fins were a precursor to the paired limbs of tetrapods, which include all land-living vertebrates – amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals and, yes, humans too. In fact, coelacanths are more closely related to tetrapods than to any other known fish species.

The youngest known fossil coelacanth is 66 million years old, leading to the assumption that these animals were long extinct. Then, in 1938, a fish with iridescent blue-green scales and four limb-like fins was caught in a trawl net off the coast of South Africa. Further investigations followed and, in 1987, ethologist Hans Fricke led a submersible expedition off the coast of Grande Comore, where he managed to capture living coelacanths on film for the first time…

Read more in this excellent BBC article here.

And still more on the story on the Gombessa Expeditions webpage, which includes this quite astonishing image and others.

Coelacanths live along steep, shelving underwater slopes. During the day, they gather in caves and come out at night to feed. And it was in these caves that Ballesta and the team found them, a minute into their first dive, would you believe - and then many times after that during the expedition. They were diving to 400ft (120m) with closed-circuit rebreathers, helium-based diluent, and a great deal of courage. These are difficult waters.

The Fish Nerds

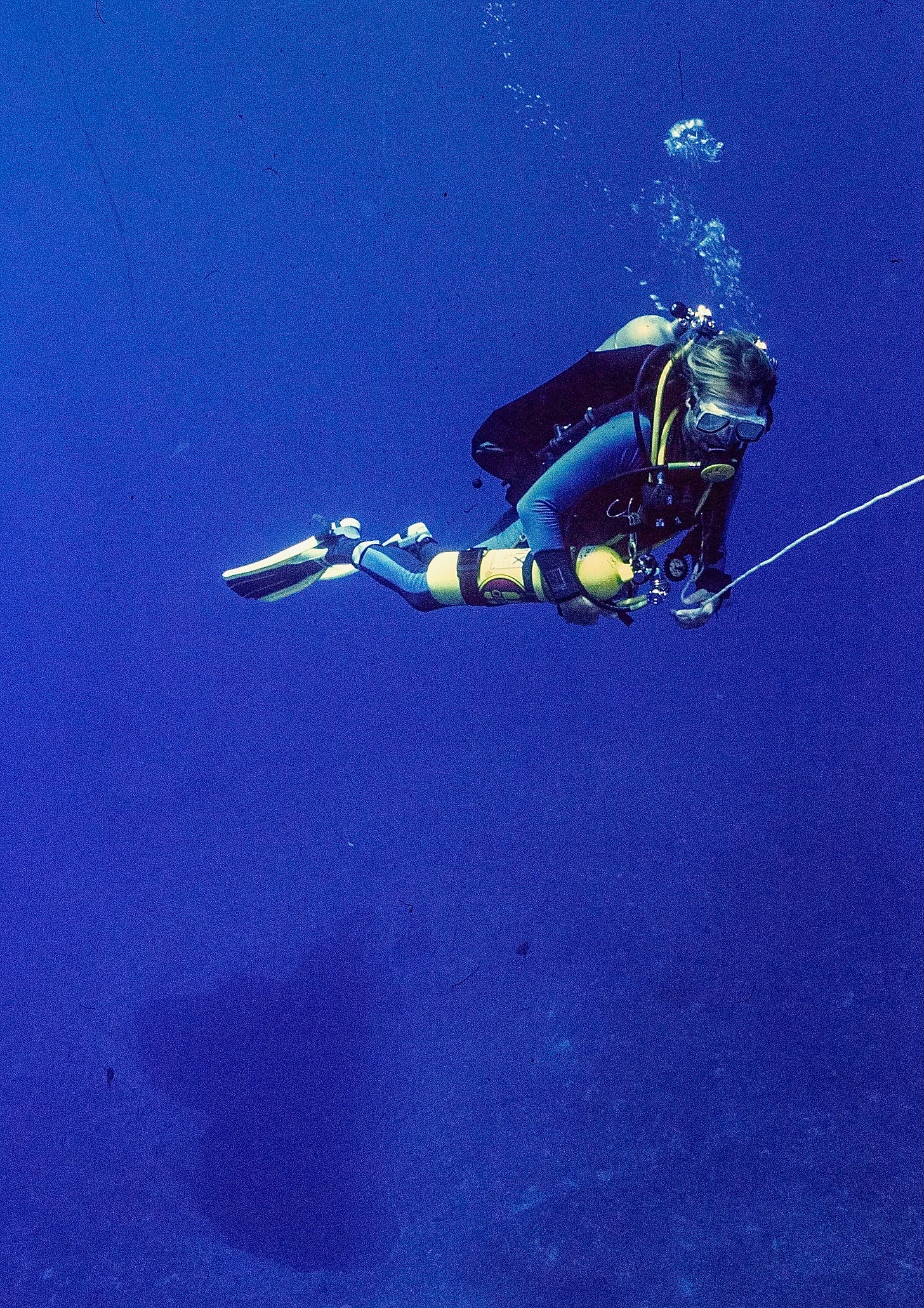

Twenty-five years ago - around the time the images at the top of this newsletter were taken - we got to the point in Guam where 200 - 220ft (60m-70m) - or twilight zone - reef wall dives with bottom times of 30 to 40 minutes became pretty much routine. We knew how to do it, we had the emergencies covered, and we had all the what-ifs squared away. We didn't take the dives lightly, but neither did we lose any sleep over them the night before.

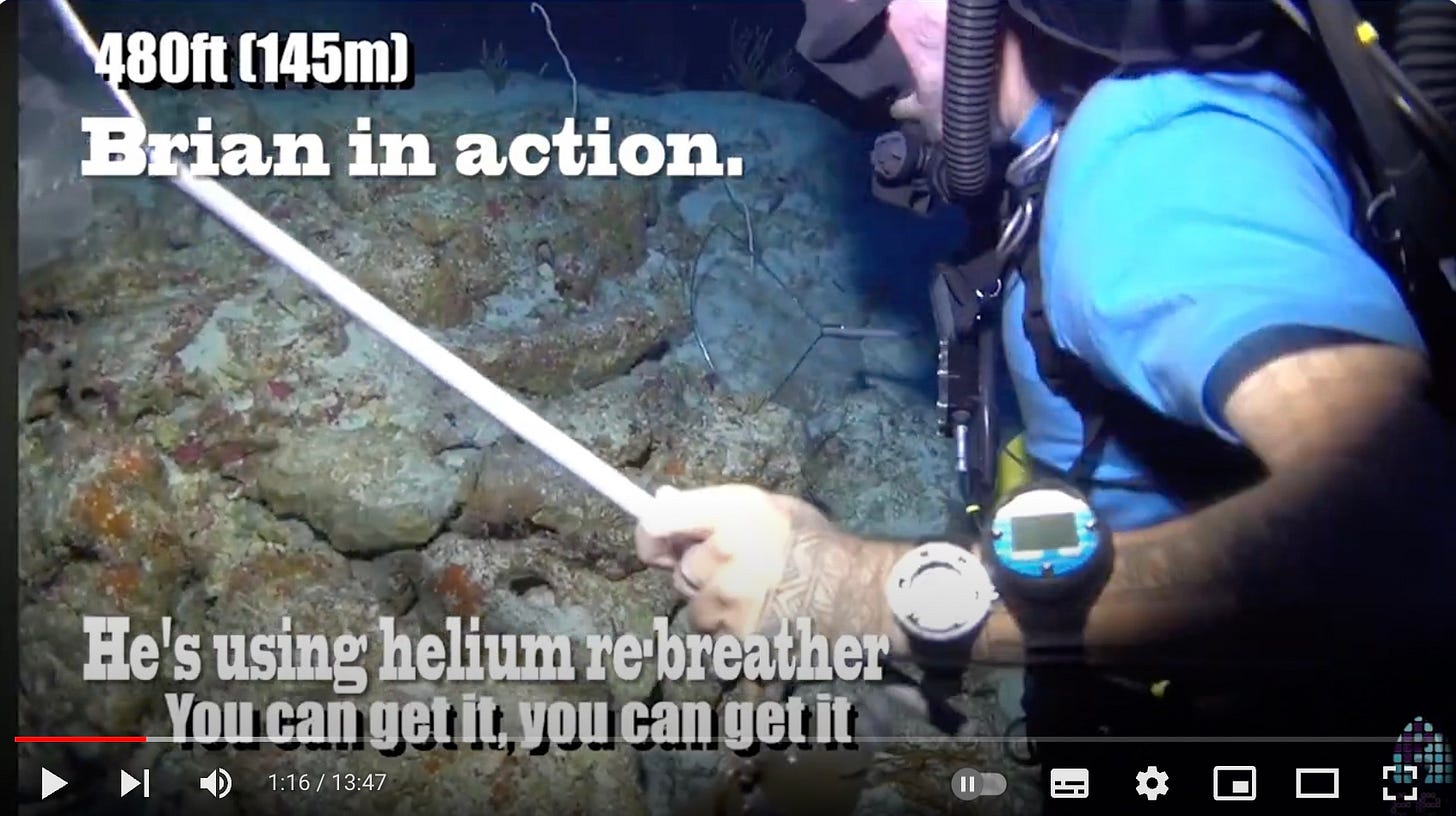

What Brian Greene, his mentor Richard Pyle, and others are doing these days is searching for new species of fish in the twilight zone in Hawaii, the Batanes, American Samoa. But now they regularly dive to 400ft (120m) plus. Brian posts little bits of video on Facebook and YouTube from time to time. One day’s clip may be a beautiful undescribed wrasse at 403ft (120m) or a 6ft (2m) tuna passing by at 360ft (110m).

He rarely refers to the depths they go to - it’s routine and not worth mentioning. I only know how deep they were because his video camera records depth in the bottom right corner of the screen. Recently, he posted bull sharks hanging out with the divers on their ascent from a 260ft (80m) dive through 78 minutes of decompression.

Back in the 1990s, we used to say that we had doubled the depth of the pool. Nowadays, 25 years on, the depth has doubled again.

Check out the video below, which is of a recent short interview with Brian. Watch not only for insight into what Brian does and how he does it but also the hilarious clip at around minute 1.15, when he and his dive buddy are deep underwater working out how to net a rare species of fish under the influence of helium at high pressure - which does very funny things to your voice.

You can follow Brian on Facebook and also via Instagram at thedeepgreene.

You will also find a superb collection of his videos here.

Bozanic on Rebreathers

You will have noticed from the above segments, if you were not already aware of this, that not only is helium key to ultra-deep diving but so are closed-circuit rebreathers.

Jeff Bozanic has been around a while and he is one of the few people who were teaching rebreather diving in the 1990s and still teaching today. He knows what he’s talking about - and in this case, writing about.

He recently wrote a piece for InDepth magazine which will have been seen by many in the sport diving rebreather community as, at worst controversial, and at best impractical - but he’s not wrong.

His main criticism was that, although most sport rebreathers on the market today are very similar in function, nevertheless, if you pass a training course to permit you to dive one brand, the certification you receive does not qualify you to dive with another model of rebreather. As a qualified rebreather diver, training agencies may allow you a free pass on some aspects of the course for a second rebreather based on the knowledge you already have, but you still need a specific C-card for each model.

For instructors, the situation is worse. They also need a card for each model and are required to either own one or have unrestricted access to every model they teach.

I stopped teaching rebreather diving many years ago, but, at the time, I had five different rebreather instructor cards. Of the five models I was certified to teach on, only one still exists, and therein lies another story, which I’ll come back to, below.

Bozanic writes:

Unlike training to pilot aircraft, automobiles, or open circuit scuba gear, current rebreather training is brand and configuration specific. What’s more, according to the recently adopted ISO training standards, instructors must wear the same unit and configuration as their students. However, given the size of the market, veteran diving educator, scientific diver and rebreather graybeard, Jeffrey Bozanic argues this approach is a recipe for extinction. Instead, he proposes we need to take a ‘systems approach’ to training and develop minimum hardware standards.

Bozanic draws a comparison with cars. If you move from petrol to electric, there are plenty of new things to learn, but you adapt. You don’t need to sit for a new driving licence.

When I was writing my book Scuba Exceptional, I referred to these issues in a chapter entitled “Rebreathers - The State of Play”. Here’s a short extract.

In 2006, twenty companies were manufacturing rebreathers for sport divers. By 2012 there were 17 companies, only 7 of which even existed in 2006. By 2018, the number of companies had fallen to 15. Ten of these were already manufacturing rebreathers in 2012 and five were new arrivals on the scene. Seven of the “new” 2012 companies had already disappeared.

These figures do not exactly paint a picture of a marketplace where shoppers can purchase with confidence. It has been very easy over the past 20 years to buy a rebreather from a company that would soon cease to exist. Most of the companies just folded suddenly, leaving purchasers without any parts or service support and a few thousand dollars worth of useless junk in their scuba shed. The numbers indicate that there has been an improvement in recent years but the possibility of making an expensive mistake still exists.

The pain of having chosen to buy a machine from a manufacturer that suddenly disappears a couple of years later is exacerbated by the fact that, under current industry rules, when you then have to buy a different model of rebreather to replace the one that has become just a defunct historical artefact, you have to take a new course or series of courses.

There are more rebreather models and companies now than there were when I did my research for the book. And some manufacturers who were operational then have since fallen by the wayside.

Many are small businesses and in his article, Bozanic fears for them.

While it may seem that certification programs designed to teach the operation of single systems to end users may seem prudent and effective, the total number of divers trained in any single system will not reach the critical mass necessary for any given rebreather company to remain in business. It may seem “safe,” but given the fragmentation and limited numbers, I am afraid that we will be certifying ourselves into eventual extinction. I would hate to see that happen.

But he doesn’t despair. Instead, he has given the situation a lot of thought and sets out several ideas - paths that manufacturers and training agencies could follow - to avert disaster and sustain a healthy sport rebreather market.

It’s an excellent piece and kudos to InDepth for publishing it. Well worth reading.

Becky Kagan Schott: Explorer

Becky Kagan Schott has used rebreathers, mixed gas and all the accoutrements that have come with the development of extreme scuba diving to expand her horizons, scuba diving horizons and share some truly astonishing places with her audience.

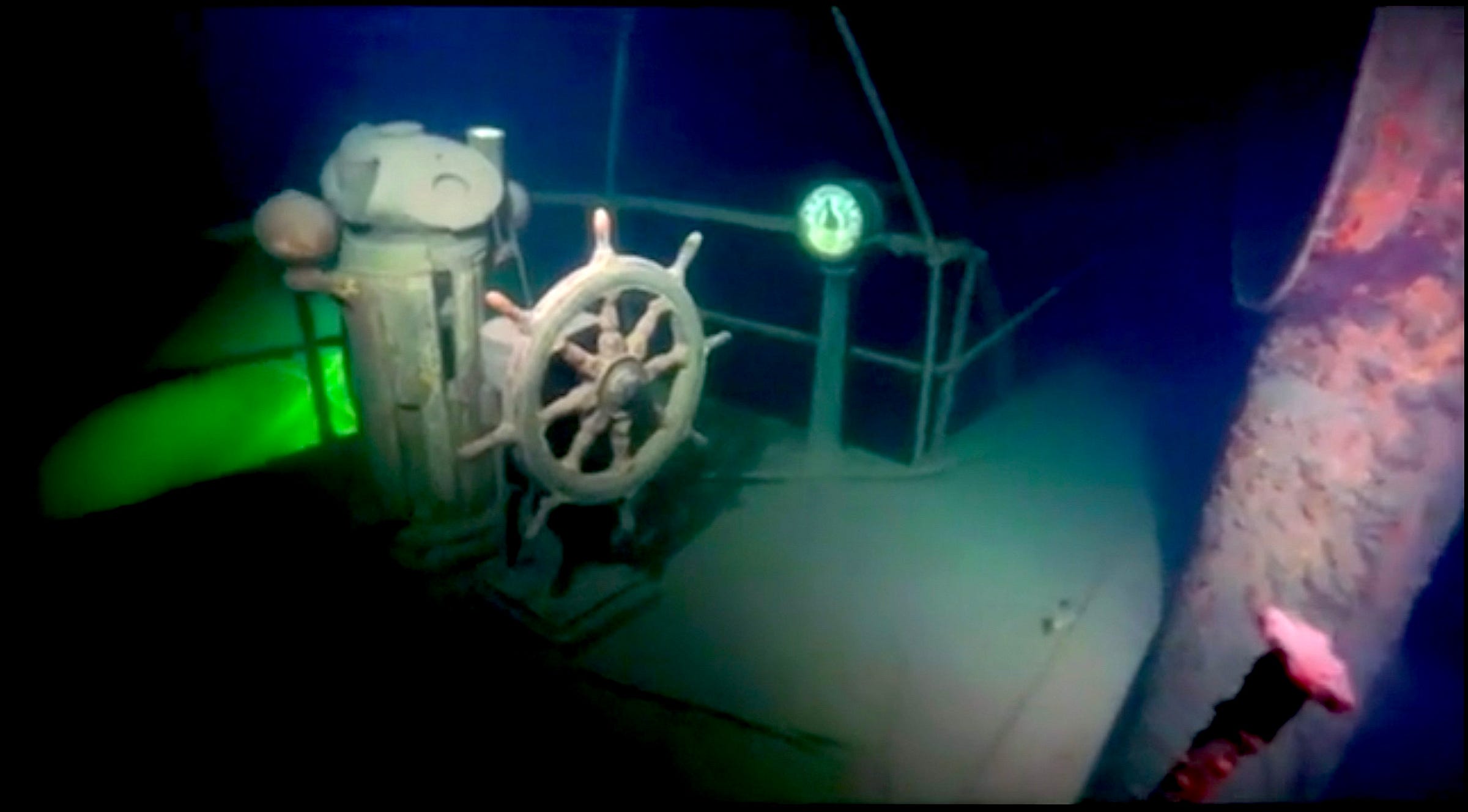

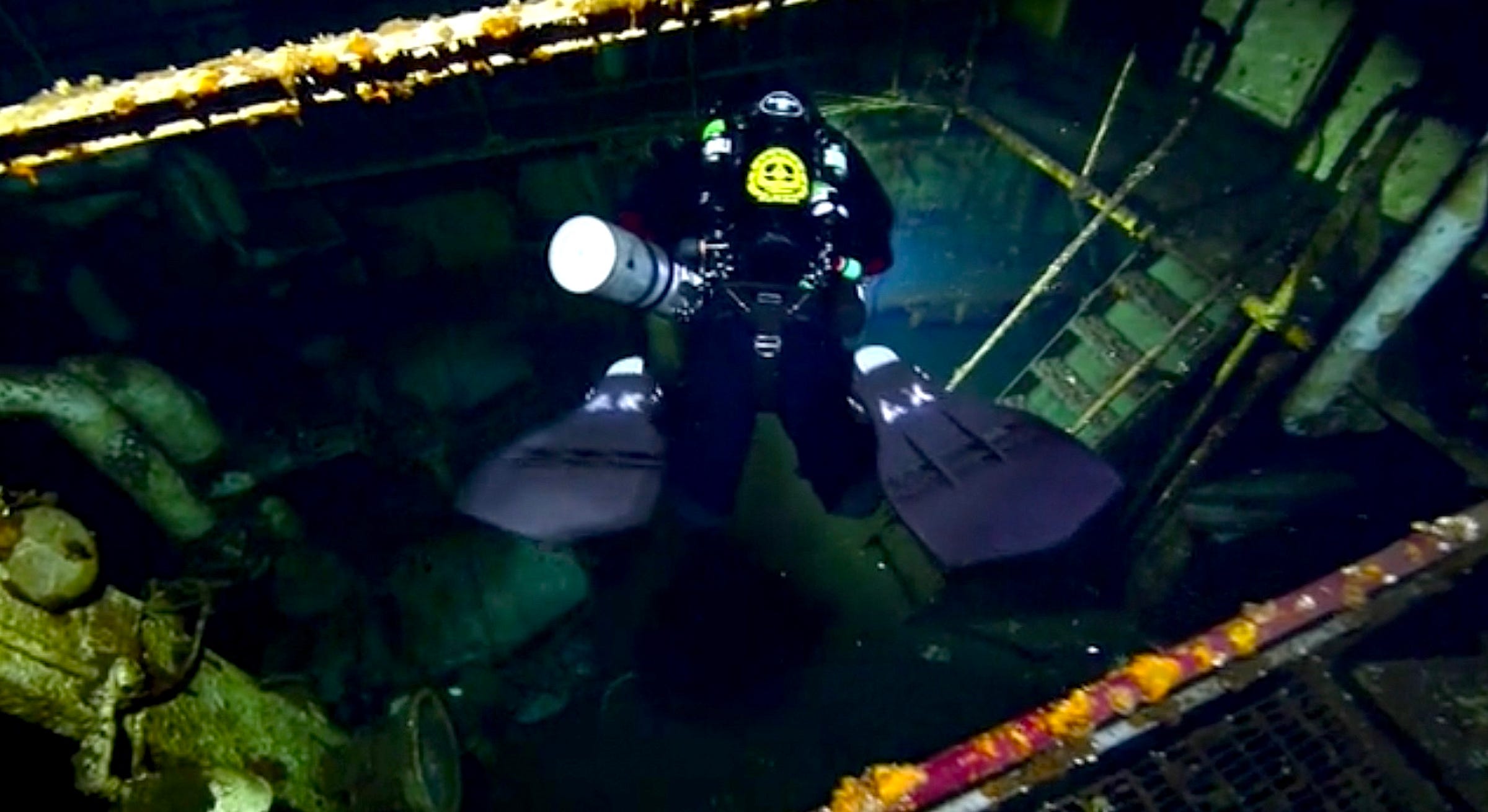

In the last issue of Scuba Conversational, I mentioned the deep Great Lakes shipwrecks. It was Becky’s photographs and video that first revealed these sunken time capsules to me.

In this video, she takes us on a dive on the Gunilda, one of the most beautiful of the historic ships lying down there in the darkness. This is a 6-minute insight into how you get incredible footage like this. Everything is against you and there are so many problems to overcome in the short time available. It all has to go right.

You can find more videos here on her YouTube channel of other places she has been and filmed - including Antarctic icebergs, inside an Alaskan glacier, the dentist’s surgery on the USS Saratoga, sunk in the Bikini island atom bomb tests, polar bears, walruses, leopard seals, you get the idea. If it’s deep, cold or difficult, she goes there, dives there, shoots astonishing videos and brings it all back.

Be warned, you can lose yourself for a while on this page.

Last but not Least

Finally for this issue, anyway, and in keeping with the theme, I highly recommend - whether you are a deep diver or not -that you download and keep this in your online library - and go through it if you have time.

This is the official record of a watershed moment in our sport and the papers presented at the workshop make for fascinating and essential reading for any diver.

When I was writing Technically Speaking, documents like this were my gold dust. I had kept a few bits and pieces, and others had been posted online over the years. I was lucky that I had friends and friends of friends who had held onto their copies of meeting records and notes and were willing to share them with me.

See You Next Time

Anyway, that’s all for this issue of Scuba Conversational. I hope you enjoyed it.

See you again for issue #66 next month.

Safe diving!

Hi Simon,

Pringle night saved by deep beginnings and funny and very interesting video of Brian Greene.

Thank you

Mahmut

This is the high-level survey of the current state of deep diving I've been wanting to read for years, Simon. Thanks for writing it and making this information available.