Scuba Conversational - Issue #64: Beginnings

Beginnings

Following my leading article in the last issue of Scuba Conversational about how I learned to dive in the Sultanate of Oman, my pal Jerry Yip sent me a copy of the diving logbook he used when he did his first diver training with what was then the Malayan Sub Aqua Club – which took all its standards and procedures from the British Sub Aqua Club (BSAC).

Here’s Jerry - back row, far right - at our rebreather training course in Pattaya a while ago.

His book was, as he guessed, identical to the logbook I was given when I first signed up to become a diver.

It lists all the skills we had to master at various stages of the process of learning to dive and I thought you might be entertained by a quick rundown of the process.

I’ll intersperse the text with pictures of people learning to dive much more recently.

***

So, turning the dial back to 1981…

On day one, to prove we were comfortable in the water, we were asked to:

1. Swim 200m (yds) with any stroke (not backstroke) without stopping.

2. Swim 100m backstroke without stopping.

3. Swim 50m wearing an 11lb (5kg) weightbelt.

4. Float on your back for 5 minutes.

5. Tread water with your hands above your head for 1 minute.

6. Recover six objects from the bottom of the pool at the deep end (one dive per object).

Then, in the next session, we learned how to use what was referred to as “basic equipment”, i.e. mask, fins and snorkel.

We practised for a week or two in a swimming pool under the supervision and guidance of an instructor, and when we were ready, we had to perform the following “primary tests” all together in one session under the watchful eye of a club examiner.

1. Throw the mask, fins and snorkel into the deep end, then dive for each item in turn and put it on at the surface.

2. Fin for 200m (220 yds), surface diving every 25m (27 yds).

3. Tow another snorkeller for 50m (55 yds), while delivering emergency breaths, then land the body and continue rescue breathing.

4. Do three forward rolls and three backward rolls in the water (you can take a breath between rolls).

5. Fin for 15m (16 yds) underwater.

6. Hold your breath for 30 seconds underwater.

7. Fin for 50m (55 yds) wearing a 5kg (11lb) weightbelt.

8. Release the weightbelt in the deep end of the pool and remove your mask.

9. Fin for 50m (55 yds), face submerged, using the snorkel but no mask.

10. Then replace the mask, surface dive, recover and refit the weightbelt, and give an OK signal.

11. Fin a further 50m (55 yds) wearing the 5kg (11lb) weightbelt.

On successful completion of these tests, we had to attend at least three club dive trips as snorkellers, during which we would perform at some point an open-water test. This consisted of a 500m (550 yds) snorkel swim, including a surface dive to a depth of 7m (23ft), then the rescue of another snorkeller, towing them for 50m (54 yds) on the surface.

There was also a series of lectures to attend, covering sinuses, circulation and respiration, hypoxia, anoxia and drowning, rescue and resuscitation, signals and surfacing, exhaustion, exposure, diving suits, protective clothing and ancillary equipment.

And after all that, we would achieve the rating of snorkel diver. We hadn’t even touched a scuba cylinder yet, but with the approval of the club diving officer, as snorkel divers, we could now “progress to pool aqualung training”.

In this part of the programme, we had to complete “a course of theory and practical training” at the end of which there would be two groups of tests, taken together in one session.

These were the tests:

1. Fit the harness and regulator to a cylinder. Test and adjust as necessary.

2. Sink all the equipment into the deep end of the pool. Dive down and put the equipment on.

3. Take the regulator out of your mouth underwater. Replace it and clear it. Do this three times.

4. Remove your mask underwater, replace it and clear it, again three times.

5. Do three forward and three backward rolls underwater.

6. Demonstrate buoyancy control by adjusting your diving level with the depth of your respiration. Breathe out hard and lie on the bottom of the pool. Then lift off the bottom using controlled inspiration.

Then:

7. Fin 100m (110 yds) on the surface as follows:

a) 50m (55 yds) alternating between snorkel and regulator

b) 50m (55 yds) on your back wearing the aqualung but using neither snorkel nor regulator

8. From the deep end of the training pool, surface, remove the regulator, put your snorkel in and give the OK signal. Do this three times.

9. Share aqualung at depth with a companion at a depth of 3m (10ft) or less. Establish buddy breathing, then fin 25m (27 yds) providing air and 25m (27 yds) receiving air. (These were the days before octopus regulators: a diver only had one second stage.)

10. Fin 50m (55 yds) underwater in a blacked-out mask either guided by a companion or following a rope.

11. Fin 50m (55 yds) submerged at speed, ending up in the deep end where a companion diver lies, simulating insensibility. Release both weight belts, bring the body to the surface and tow for 25m (27 yds), incorporating rescue breathing.

12. Remove both sets of equipment in the water, land the body and continue rescue breathing.

Having demonstrated mastery of these exercises, we could “progress to open water aqualung training”.

You will have noted that, at this point, several weeks into our diving course, we have still not dived on scuba outside of a swimming pool!

Once we eventually made it to the ocean, we then had to do 10 qualifying dives in at least five different places and on 5 different dates. This series of dives had to include 5 of 8 qualifying conditions/environments, as follows:

a) A shore dive along a shelving bottom

b) A dive from a boat

c) A dive in freshwater

d) A dive in moving water (1 knot minimum)

e) A dive in seawater

f) A low-visibility dive (less than 2m (6ft))

g) A dive to 25m (82ft)

h) A dive on a reef or coral outcrop.

After doing all this, attending lectures on physics, burst lung, emergency ascent, air cylinders and endurance, underwater navigation, decompression sickness, nitrogen narcosis, CO poisoning, oxygen poisoning, deep diving and other topics, then completing a final exam, we were finally declared to be third-class divers!

And, at least in my case, embark on a life-long career. :-)

By the way, you may recognise one of the pool pictures above as part of the series that gave us the cover image for Scuba Physiological.

It was the fuzziness (and fizziness?) of the image that - I thought - made it a good choice for a book discussing issues on which there is so little certainty.

Meaningful Media

The rest of this issue is devoted to highlighting films, books and articles on scuba diving that have crossed my radar screen and that you may wish to view, buy, browse, or just be aware of.

Several recent short films have either made me stop and think - or blurt out “Wow!” and replay. See what you think.

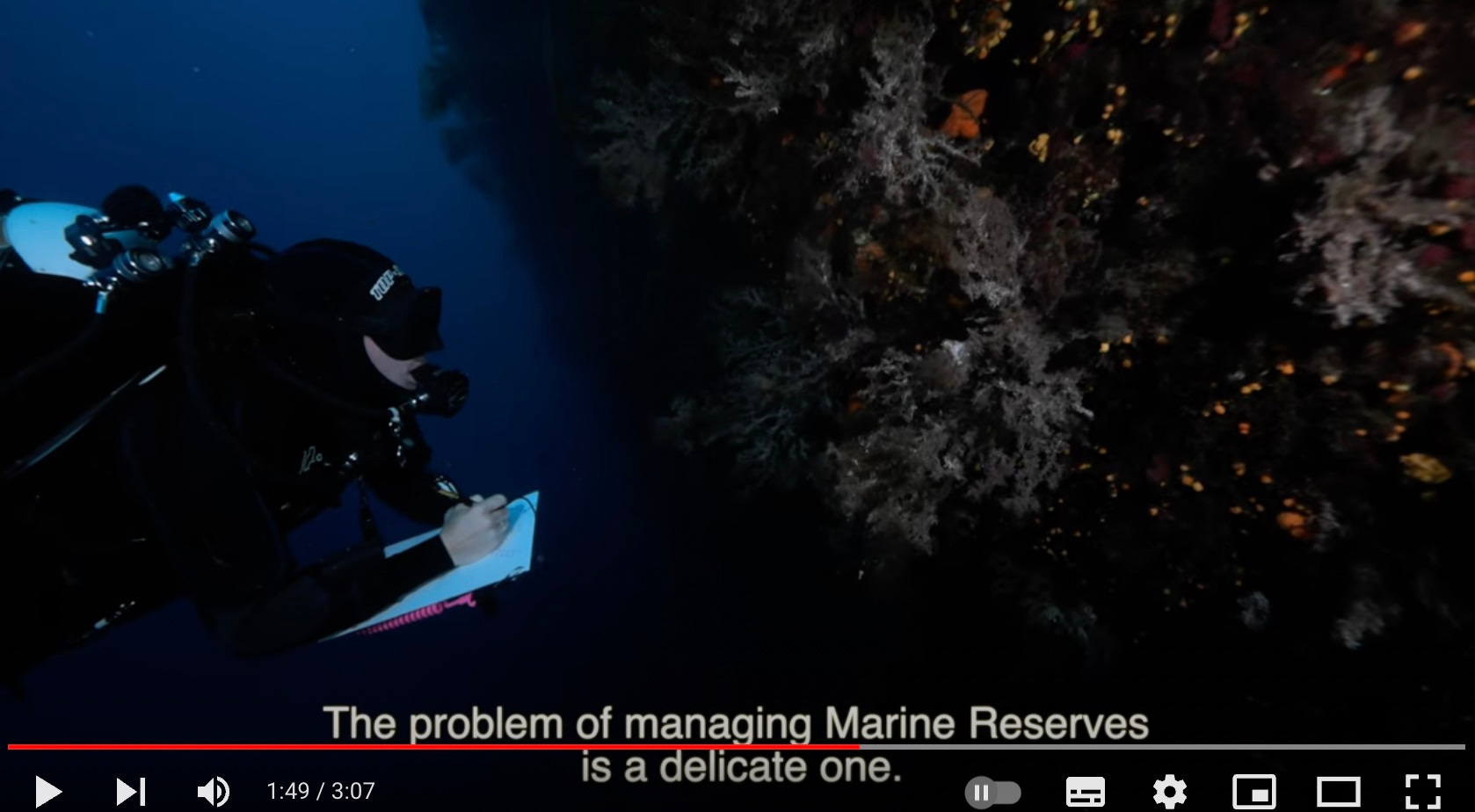

Marine Preserves

The first is by Lorenzo Moscia, whose superb over/under shot is featured above.

His latest video, released in July, is a short piece on the importance of marine reserves. It makes the two crucial points that

There aren’t enough of them, and

Those that have been created are sometimes too small to do what they are supposed to do - that is, protect marine creatures, some of which are highly mobile and frequently stray beyond the invisible reserve boundaries, especially when these boundaries are not very wide.

Greenpeace Liguria 2024 Expedition

This is a common complaint worldwide. Political pressure produces compromises.

Here is an extract from my Dive into Taiwan book about the Penghu Islands, which lie in the straits between Taiwan and continental Asia.

The most interesting part of Penghu for divers is the South Penghu Marine National Park, an MPA in the far south of the archipelago, where a large rectangle of ocean around four sparsely populated islands, Xipingyu, Dongyupingyu, Xijiyu and Dongjiyu, (the suffix “yu” means island) has been designated as a no-take zone. Unlike many MPAs and marine parks around the world, this one is well protected by a highly assiduous official with a reputation for being uncompromising, who lives and works nearby on the island of Jiangjunaoyu. He has a patrol boat and powers to arrest and impound, but his greatest asset is his power of persuasion. Since the MPA was set up in 2014, he has gradually managed to convince all the islanders to get behind it – a significant achievement.

In the early days of the project, as you might imagine, there were rumblings of opposition and even occasional violent protests, principally from fishermen who feared that the MPA would deprive them of their livelihood. They were asked to be patient and promised that the MPA would not adversely affect their business. On the contrary, they were told, hauls of fish from the sea around the MPA would actually improve, as a consequence of fish stocks increasing inside the MPA. When the fishermen discovered, very quickly, that this was indeed the case, they stopped complaining and concentrated on fishing.

Fish counts within the MPA have doubled year on year since its inception and the catches made by south Penghu fishermen have grown similarly. The fishermen are not the only ones who have benefitted. More fish means happier divers and snorkelers and when divers and snorkelers are happy, they tell other divers and snorkelers. More dive tourism provides further employment for the people of the islands and greater income for local stores, restaurants, guesthouses and scooter rental outfits. The MPA is the gift that keeps on giving for everybody.

This is what MPAs do for people all over the world and it is worth expanding on the subject here, because, as you will read later in this guide, Penghu’s experience could serve as a template that people on other outlying Taiwanese islands could follow, to solve their own problem with dwindling fish numbers.

The Penghu MPA is what the scientists call an enforced, (that is, strongly protected) MPA, in that no commercial extraction is permitted, only limited recreational activities are allowed and there is someone around who makes sure the rules are not broken. The benefits of establishing such MPAs have been well-documented all over the world. The total biomass within the area increases many-fold and fish and invertebrates such as clams and lobsters grow larger and produce more young. As in Penghu, fisheries profit from the abundance of life inside the MPA spilling over into the waters around it.

It also seems that marine life in an MPA becomes more resistant to environmental change and can recover more quickly from an environmental disaster. For instance, when, a few years ago, abalones in the Gulf of California started dying because of a reduction in the level of oxygen in the surrounding waters, it was the abalones in the local MPA that survived best, recovered most quickly and ended up repopulating the entire area. From this, it is logical to hope that preserving healthy marine life in protected zones may be a way to help ocean ecosystems survive whatever calamities the present climate change event ends up throwing at them.

Dongjiyu and Xijiyu are the main islands that constitute the Penghu Columnar Basalt Nature Reserve Nanhai, which means that, when you visit the MPA, as well as some great, fishy diving, you get to experience the best of the geological wonders of the islands too.

Big Animals on Closed Circuit

In the Galapagos Islands and various places in our vast ocean world - Izu Japan, Banda Indonesia, Malpelo, Cocos and others - if you are lucky, you can see hammerhead sharks. We have all seen the footage of large schools meandering by while divers watch on, but we know how wary and skittish these wonderful animals are - chase them to get closer, and suddenly they are gone, and you are swimming - or being dragged along by a fast current - in an empty ocean.

Wouldn’t it be astonishing if you could just be resting on the sand and, out of nowhere, a group of hammerhead sharks would approach you, oblivious of your presence, saunter towards you and swim right over the top of you, so close that you could reach out and touch - but of course you don’t - and have to spin your camera around so they don’t fill the frame?

Well, if you are on a rebreather, this can happen, as we see from this video footage shot by Pete Mesley, shot on one of the Galapagos trips that he organises. You are the viewer - the person with the camera - and as the film begins, it’s just you and your dive group, a sandy white seabed and a turtle cruising along. Then things get a lot busier. It is beautifully edited and only lasts just over one minute, but it takes your breath away.

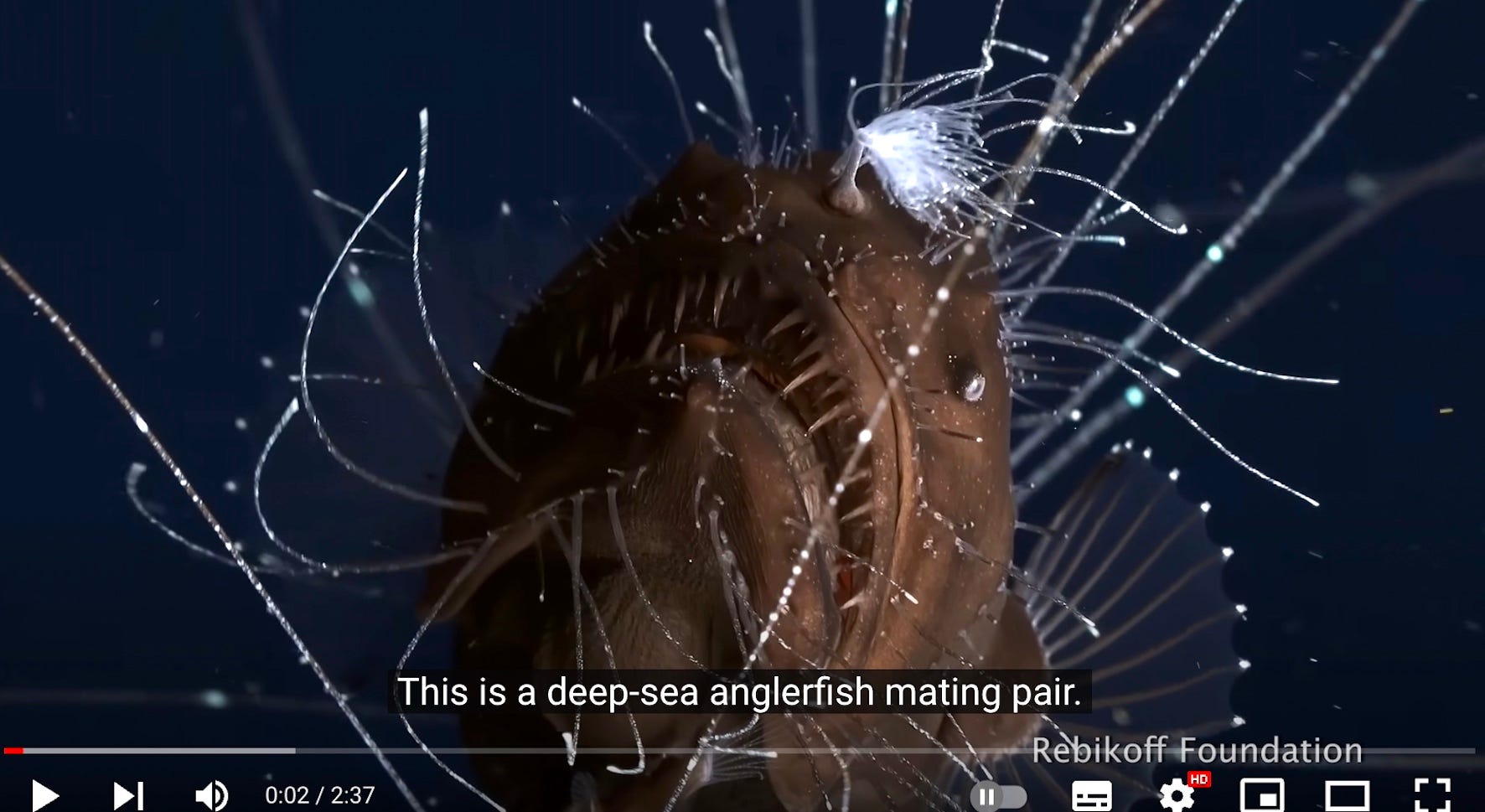

“I’ve Never Seen Anything Like It”

Another piece of film that will leave you open-mouthed with amazement is this video footage of angler fish mating at a depth of around 800m (half a mile) off the Azores.

This image links to the YouTube video

You can find more information on this page on Science.org - which allows non-subscribers three page views every 30 days.

The text begins:

Anglerfish, with their menacing gape and dangling lure, are among the most curious inhabitants of the deep ocean. Scientists have hardly ever seen them alive in their natural environment. That's why a new video, captured in the waters around Portugal's Azores islands, has stunned deep-sea biologists. It shows a fist-size female anglerfish, resplendent with bioluminescent lights and elongated whiskerlike structures projecting outward from her body. And if you look closely, she's got a mate: A dwarf male is fused to her underside, essentially acting as a permanent sperm provider.

"I've been studying these [animals] for most of my life and I've never seen anything like it," says Ted Pietsch, a deep-sea fish researcher at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Find more here

I've never seen anything like it

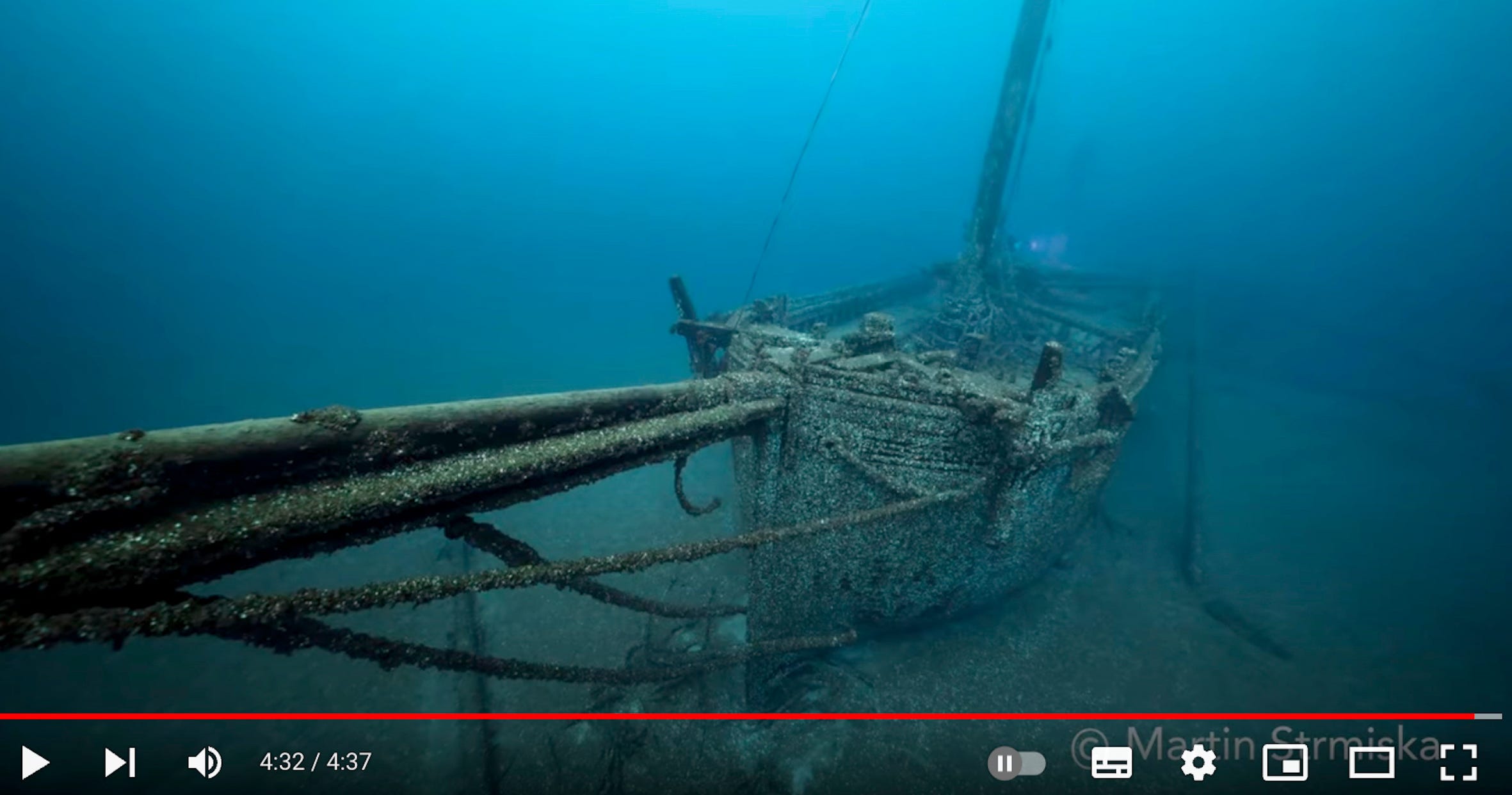

Shipwrecks of the Great Lakes

There’s a good chance you’ve seen photographs of the amazingly well-preserved shipwrecks of the US Great Lakes before. Some extremely talented technical divers have taken some wonderful photographs over the past few years, but I have seen nothing to compare with the work Martin Strmiska did this summer in Lake Huron and a couple of weeks ago, he posted a short video on YouTube that, once again, will leave you marvelling at the clarity, the lighting and the sheer quality of his production. These are deep, cold, difficult dives.

I’ll post a couple of screenshots below, but they don’t do justice to the film. Watch it on the best display you have.

Pioneers

I have a new book high on my “to read” list, which tells the tale of how scuba diving began in the Red Sea, and I’ll be buying a copy as soon as:

They publish an e-book version

We settle down and I can start buying real books again, or

The Hong Kong public library buys a copy.

This is Howard Rosenstein’s early autobiography, and it’s available now only in hardback so far via Amazon and elsewhere.

Here’s the blurb.

It’s a tale of grit, where resourcefulness and connections fueled Howard’s pioneering spirit. From Roman coins glinting on the seabed to the dark, unmapped depths, his dives unveiled sunken treasures and secrets of the past. But these weren’t just underwater adventures — they were tightrope walks between nations still at war. He braved floods, aided grounded ships, and even braved the depths of Mount Sinai itself.

Howard’s journey wasn’t a solitary one. He rubbed shoulders with underwater legends, bestselling authors, true photography greats, and even world leaders. He navigated murky shipwrecks, charmed amorous sharks, and found himself a player in the delicate dance of peace negotiations.

‘A captivating voyage through the exotic wonders of the Middle East’– Amos Nachoum

‘Howard Rosenstein had a dream that he made a reality – he built, and they came’– David Doubilet.

Through his dive centers, first in the Mediterranean and then exploding onto the Sinai scene, Howard became a pioneer of recreational diving. He shared the magic of the underwater world with a generation, igniting a passion that would forever burn, his only desire that it would never end. But peace, like the tide, comes with a change.

The extraordinary story of the entrepreneur who pioneered Red Sea dive tourism with a cast of unforgettable characters.

How a dive school in a train carriage at the edge of the desert became a global destination.

A journey of success and purpose, illustrated with 200 images by the author and others, inc. renowned underwater photographer David Doubilet.

Steve Weinman gave it a glowing review in Divernet - always a good indicator. He writes:

The rich cast of dive-dazzled visitors is part of the attraction of the book. Amid the touring dive-clubs are the photojournalists like Doubilet, wildlife enthusiasts such as ’Shark Lady’ Eugenie Clark and various diplomats, military officers and politicians with the power to make things happen. And images like that of Leonard “Maestro” Bernstein dancing on a boat in the moonlight with a burly Egyptian fisherman linger in the memory.

Then there are the colourful shipwrecks of the book’s title, familiar names now but not back in the ’70s – the likes of the Dunraven, Carnatic and Jolanda.

This book covers only the early part of Rosenstein’s life-story, before the successful Fantasea liveaboard and photography ventures that led to him becoming familiar to ever more divers.

The pioneering years ground to a halt once Egypt had taken back control of the Sinai and its emerging dive industry, but this happened only after he had devoted several years to shuttle diplomacy with Cairo, trying to ensure that the foundations he and his entourage had laid would remain and that marine-conservation standards would be maintained in the Red Sea.

These efforts were not wasted – it seems that Howard Rosenstein was always good at selling ideas. This is a fascinating story and one well told.

What appeals to me most about this book is that Rosenstein is writing for posterity about a time and place that are long gone, and those days would have been forgotten had he not recorded them. Scuba diving is a niche sport - scuba diving history is even more niche - but this is our niche and our history and I’m delighted that this book has been published.

Divernet has also produced a long piece recording some of John Christopher Fine’s memories and photographs from the time he spent with some of the early pioneers of scuba diving, Cousteau, Tailliez, Hass, Mayol, Dumas and others.

Here’s a taste of Tales of Diving’s True Pioneers. There’s some fascinating, unique material here.

It was on a cold, rainy, fog-shrouded day that Tailliez came to pay his final respects to Frederic Dumas. We arrived very early and, amid dense mist, wondered whether we were in the right place.

Of course we were – there was only one beach – but was it the right day, or had the weather forced cancellation of the memorial service?

Finally, in the distance, we heard music from a procession that had just reached the beach, from the plaza now named for Dumas, Sanary sur Mer’s most illustrious citizen.

As Tailliez and I stood in the drizzle, the cold penetrating to our damp skins, an apparition arrived out of the mist.

“Jacques, Jacques,” Tailliez’s now-hoarse voice whispered. Cousteau had arrived to pay his final respects to the man most responsible for his fame and good fortune.

The ceremony was long, yet seemed to disappear in the humility of the two remaining Mousquemers as they spoke, more to each other than to the other people assembled there.

When I wrote Technically Speaking Part 1, recalling the early days of technical diving, I was very conscious of the fact that the book might have a function beyond just telling an interesting tale. David Strike, in his review, was kind enough to say that it “charted the growth and development of an aspect of diving that ranks as one of the most important in the entire history of underwater developments…” and that it was “a book for the ages”.

Among the appendices to Technically Speaking, I included a bibliography of some of the books that I had used for reference and others that I thought would warrant a place on the bookshelves of serious divers - and diving historians.

Here is the full list, as it appears in Technically Speaking, just in case you want to copy and paste any of these books to your own list. Or you can always come back to this newsletter (#64) to review it.

It’s long, but then again, it should be.

Major Tomes

NOAA Diving Manual - NOAA (Editor Greg McFall)

The Navy Diving Manual - US Navy

Commercial Diver Training Manual - Hal Lomax

International Textbook of Mixed Gas Diving - Heinz Lettnin

The Watersports Publishing Series

Dive Computers - Ken Loyst

Deep Diving - Bret Gilliam, Robert von Maier, John Crea

Solo Diving - Robert von Maier

Mixed Gas Diving - Tom Mount, Bret Gilliam

When Women Dive - Erin O’Neill

Dry Suit Diving - Steve Barsky

Technical Diving History and Technique

An Introduction to Technical Diving - Rob Palmer

The Last Dive - Bernie Chowdhury

Technical Diving from the Bottom Up - Kevin Gurr

The Technical Diving Handbook - Gary Gentile

Technical Diving in Depth - Bruce Wienke

The Technical Diving Encyclopedia - Tom Mount and others

Exploration and Mixed Gas Diving Encyclopedia / The Tao of Survival Underwater - Tom Mount, Joe Dituri and others

Technical Diving: An Introduction - Mark Powell

A Walk on the Deep Side - John Kean

Doing it Right - Jarrod Jablonski

Into the Abyss - Rod MacDonald

Cave Diving

Into the Planet - Jill Heinerth

The Essentials of Cave Diving - Jill Heinerth

The Darkness Beckons - Martin Farr

Raising the Dead - Philip Finch

Beyond the Deep - Bill Stone, Barbara von Ende, Monte Paulsen

Caverns Measureless to Man - Sheck Exley

Aquanaut - Rick Stanton

Blind Descent - James Tabor

Drawn to the Deep - Julie Hauserman

The Cave Divers - Robert F. Burgess

Fatally Flawed - Verna van Schalk

Wreck Diving

Beyond Sportdiving - Bradley Sheard

Deep Descent - Kevin F. McMurray

The Advanced Wreck Diving Handbook - Gary Gentile

Shadow Divers Exposed - Gary Gentile

Complete Wreck Diving - Henry Keatts, Brian Skerry

40 Dives, 40 Dishes - Al and Freda Wright

Shadow Divers - Robert Kurson

Shipwreck Diving - Daniel Berg

Mystery of the Last Olympian - Richie Kohler

Lake Erie Technical Wreck Diving Guide - Erik Petkovic

The Shipwreck Hunter - David L. Mearns

Deeper into the Darkness - Rod MacDonald

Rebreather Diving

Mastering Rebreathers - Jeff Bozanic

The Basics of Rebreather Diving - Jill Heinerth

The Third Dive - Robert Osborne

Breakthrough - John R. Clarke

Diving Skills, Strategies and Science

The Six Skills and Other Discussions - Steve Lewis

Staying Alive - Steve Lewis

Under Pressure - Gareth Lock

Deeper into Diving - John Lippmann and Simon Mitchell

Deco for Divers - Mark Powell

Deep into Deco - Asser Salama

Between the Devil and the Deep - Mark Cowan and Martin Robson

Diving Physiology in Plain English - Jolie Bookspan

General Deepness

Deep - James Nestor

Last but not Least

Finally, for this newsletter, here are a few links directing you to some of my recently published articles and one by Sofie, just in case they have escaped your notice amongst the daily barrage of information that comes your way.

X-Ray 127 has a superb cover image and story about Yap by David Fleetham and a fascinating feature on epaulette sharks, as well as plenty of other good stuff. My Scuba Confidential column in this issue is called Dive Culture Confusion. This is the background.

"A friend recently sent me a detailed account of the Red Sea dive trip he joined in 2022. Lots of people send in “it happened to me” stories. They have read my books and know I like tales like this. I dissect them, feast on them, and then regurgitate them as magazine articles or newsletter anecdotes with the idea that divers might learn something from them.

Some reports tell the story of a problem-free fortnight in paradise, extolling the virtues of a destination or dive operator. Others talk about a dive that went wrong or a dive centre that did not live up to expectations.

And then, there are the stories that seem relatively unexciting at first but open an entire Pandora’s box of issues when you delve deeper. These are the stories I enjoy the most, and this one is an excellent example."

The cover picture above links to the X-Ray Magazine website where you can download the whole magazine - which I thoroughly recommend.

But, if time is pressing, you can read my article here. You can also download a PDF from the same page.

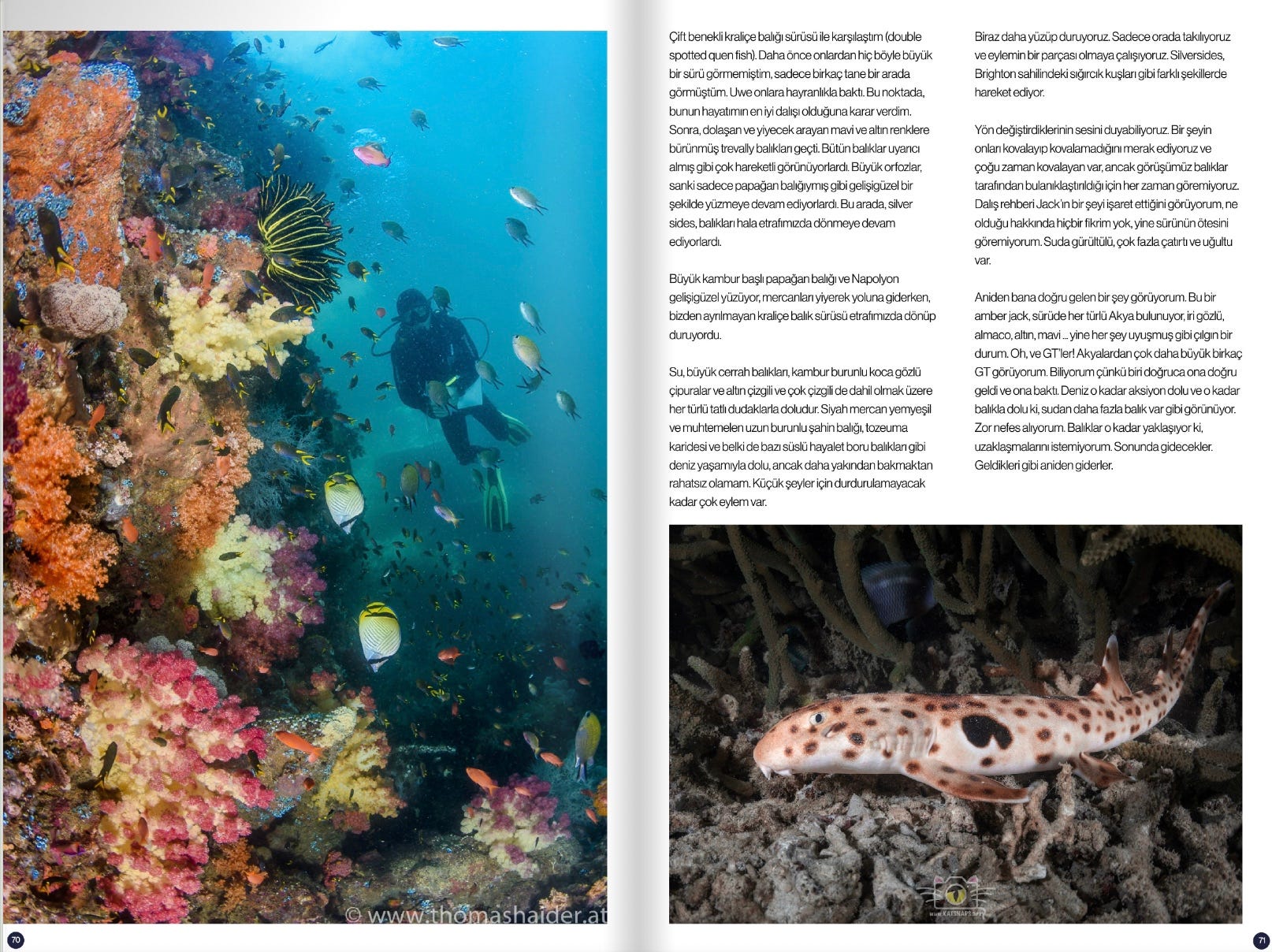

Earlier this year, Triton editor Mahmut Suner spotted Sofie’s article about our trip to Triton Bay Divers (TBD) in West Papua and asked if he could translate it into Turkish and feature it in his magazine (also named Triton). Sofie agreed, Mahmut contacted Leeza at TBD for some photos, she supplied some wonderful shots taken by world-class photographers, and the piece even made the front cover.

You can view the whole of issue 12 of Triton online here. Even if you don’t read Turkish, it’s well worthwhile. There are some excellent pictures of dive sites rarely covered by the UK or US diving media.

Here is Sofie’s article in all its glory.

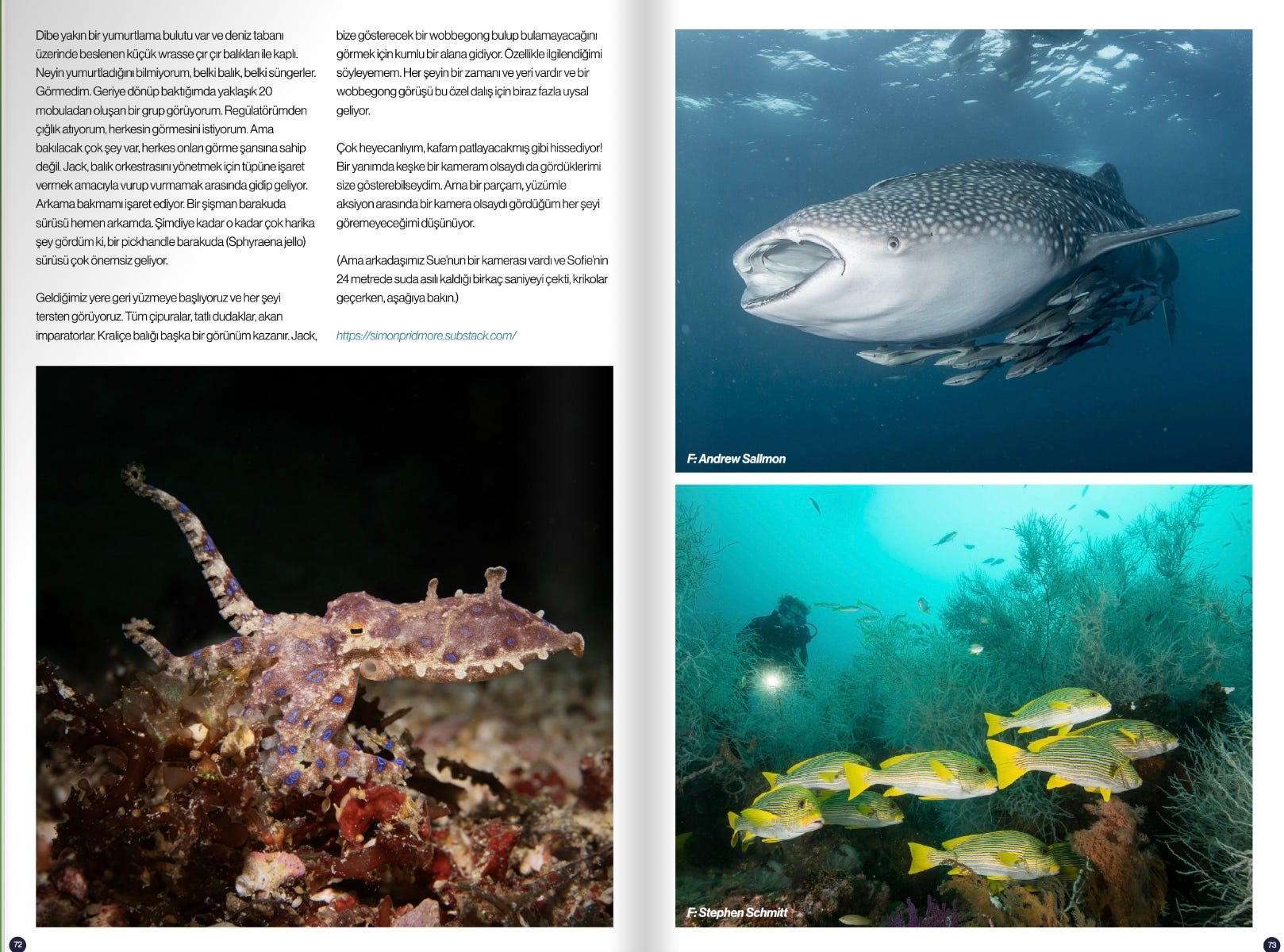

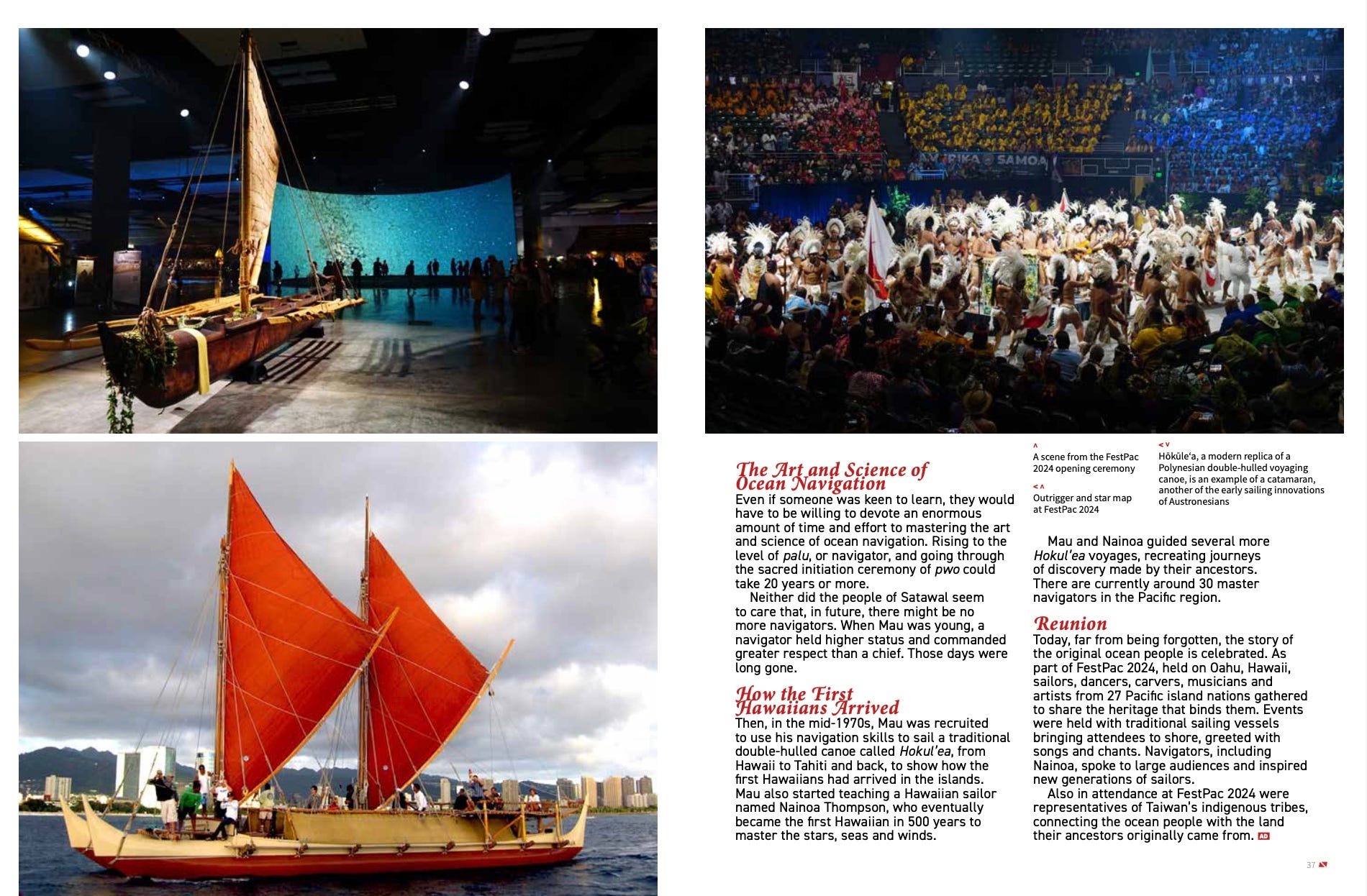

A superb shot of a diver surrounded by sharks adorns the latest issue of Asian Diver, but my article in this issue is about something entirely different. Asian Geographic Magazines Senior Editor Sol Foo heard about our trip to Hawaii to attend the Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture (FestPac) in June and asked if I could come up with an ocean-themed piece.

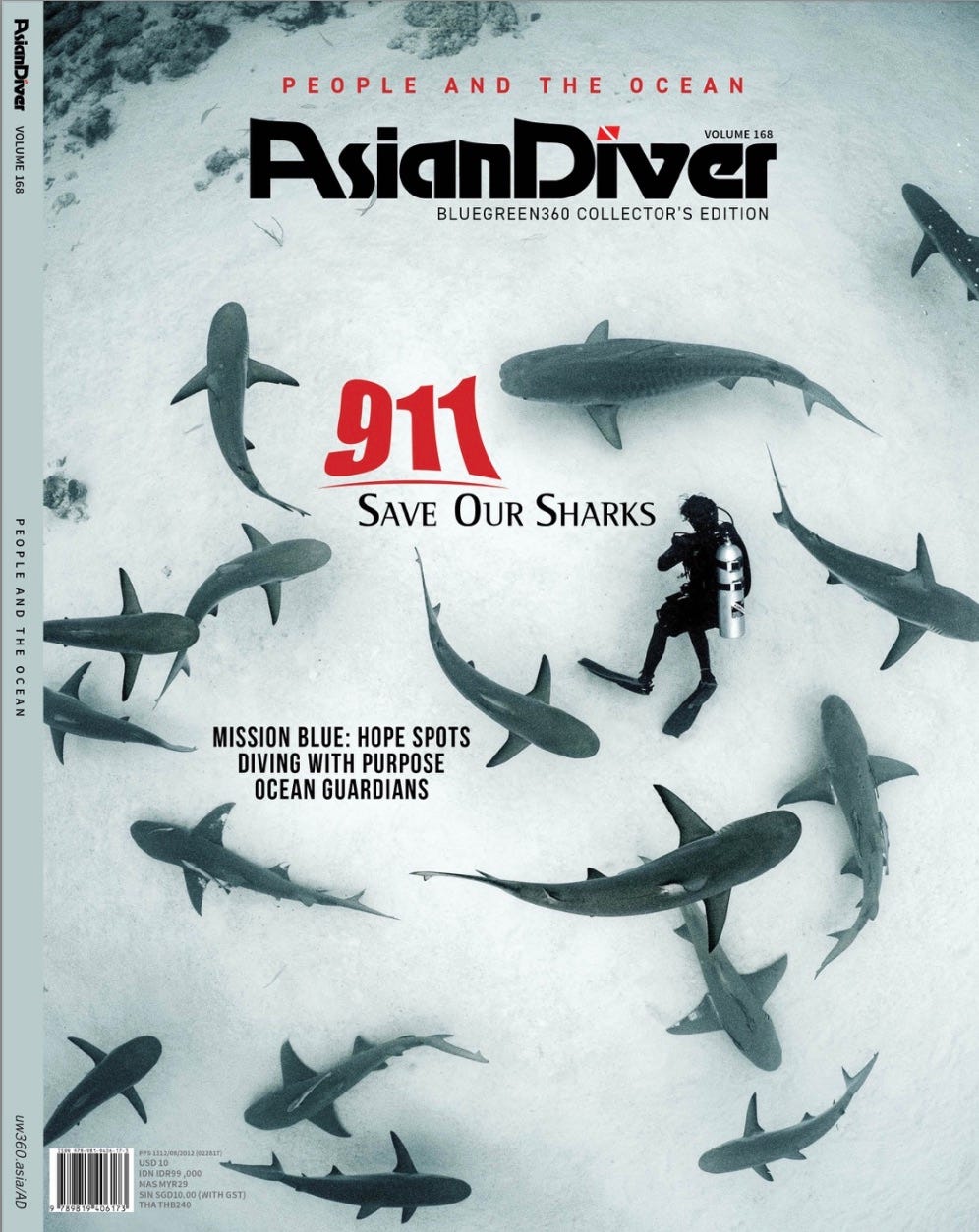

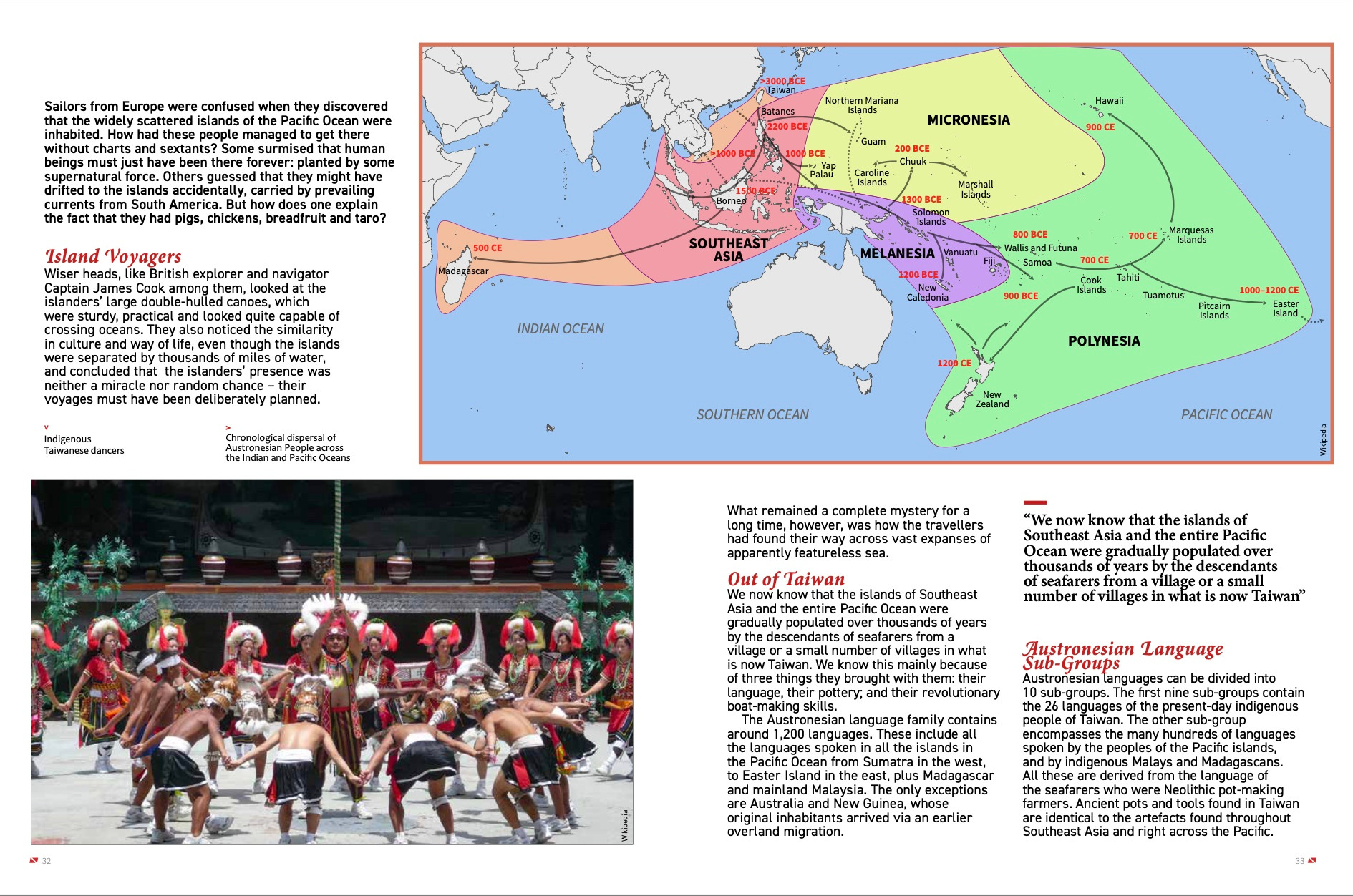

I decided to combine pictures from this spectacular explosion of music, art and dance with the story of how the ancestors of all the Pacific people made their way to the islands in the first place, by crossing vast stretches of ocean, and how the ocean connects rather than separates them.

The story begins with a big question - several questions in fact…

Sailors from Europe were confused when they discovered that the widely scattered islands of the Pacific Ocean were inhabited. How had these people managed to get there without the charts and sextants that the Europeans had used?

Some imagined that human beings must just have been there forever: planted there by some supernatural force. Others guessed that they might have drifted to the islands accidentally, carried by prevailing currents from South America. But then, how to explain the fact that they had pigs, chickens, breadfruit and taro?

Wiser heads, British explorer and navigator Captain James Cook among them, looked at the islanders’ large double-hulled canoes, which were sturdy, practical and looked quite capable of crossing oceans. They also noticed the similarity in culture and way of life on islands separated by thousands of miles of water and concluded that the islanders’ presence was neither a miracle nor a random chance. Their voyages must have been deliberately planned. What remained a complete mystery for a long time, however, was how on Earth the travellers had found their way across vast expanses of apparently featureless sea.

If your local bookshop or airport bookseller (the only place we can find magazines these days) doesn’t stock Asian Diver, you can find it here. Or you can always subscribe.

Finally, for this month’s Scuba Conversational, here’s the true story of what happened to Richard and Florence, the reason Richard got into trouble, how Florence rescued him and why it all happened in the first place. It’s in the latest edition of DIVELOG surrounded by the usual excellent cornucopia of unmissable content.

See You Next Time

That’s all for this issue of Scuba Conversational.

See you again for issue #65 next month.

Safe diving!

Gosh, just like PADI (sort of). Thanks, Simon. When I was first diving, I had the experience (privilege) of diving with some BSAC-trained divers on several occasions, which were themselves educational experiences. My own training (at Sao Wisata, Flores) was based on the CMAS system, but my instructor—who had grown up as a spearfisher and hookah diver on same reefs) made up some of difference and filled in some badly missing pieces.

Nice surprise. Thank you. I am reading and watching the films for the last hour they are great. I love the Great Lakes film. I dove there in 1975. Lovely place.

Regards to you both,

Mahmut