From the Edge of the Deep Blue Sea

A two-hour fast ferry ride from Taiwan’s southeastern port of Fugang, Lanyu - Orchid Island - rises from the sea, a jagged, battered remnant of a long-extinct volcano and the sole homeland of the Tao people. It is a wild place: a land of coastal volcanic plains, tall, windswept, emerald-green cliffs, and an almost impassable highland interior.

Ancient lava flows slope down towards the ocean, where they merge with fringing coral reefs to create the topography that so fascinates visiting divers. The scenery is reminiscent of other geologically turbulent, edge-of-the-world places like Iceland.

But this is indubitably a Pacific Island, and the Tao are Pacific islanders. The men fish and build houses and boats, while the women plant taro and weave, just as they do throughout Micronesia and beyond. Like many island peoples, they have developed a unique, fascinating culture based on the world around them.

The surrounding seas are the hub of the Tao universe and the most important creatures in the ocean and the focus of the Tao religion are flying fish. The canoes they go out on to catch these fish are unique (and highly Instagram-worthy).

Orchid Island is a far-flung frontier and it sees far fewer divers than Taiwan’s other scuba hotspots, with the possible exception of South Penghu. There are two main reasons for this. First, although there are a couple of highly professional dive operators on the island, the diving infrastructure here is less well-developed than on neighbouring Ludao (Green Island). Second, the island’s remoteness makes coming here for a diving weekend more difficult and expensive than more easily accessible options like Kenting and the Northeast Coast.

As you can see the water is the bluest of blues and the visibility is extraordinary.

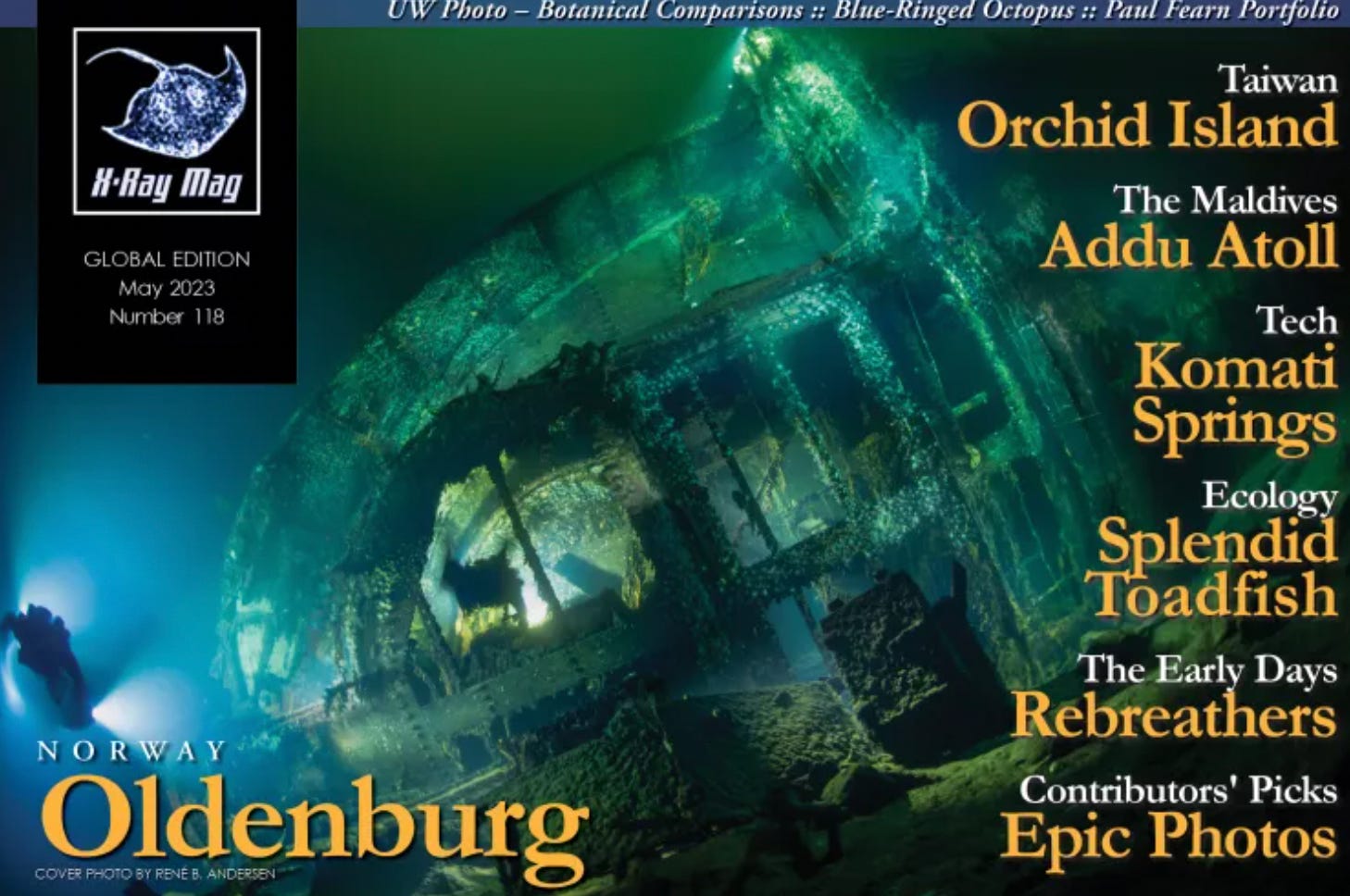

I recently published a feature on scuba diving around Lanyu/Orchid Island in X-Ray magazine. See

https://xray-mag.com/content/orchid-island-dive-taiwan-part-5

Or you click below to download a PDF of the full article featuring more amazing images by Kyo Liu and Willy Hsieh.

And here’s the link to a page where you can download the whole issue.

In the last Scuba Conversational, I mentioned my article on the early history of sport rebreather diving. There is another piece in X-Ray 118 that is particularly worthy of your attention too.

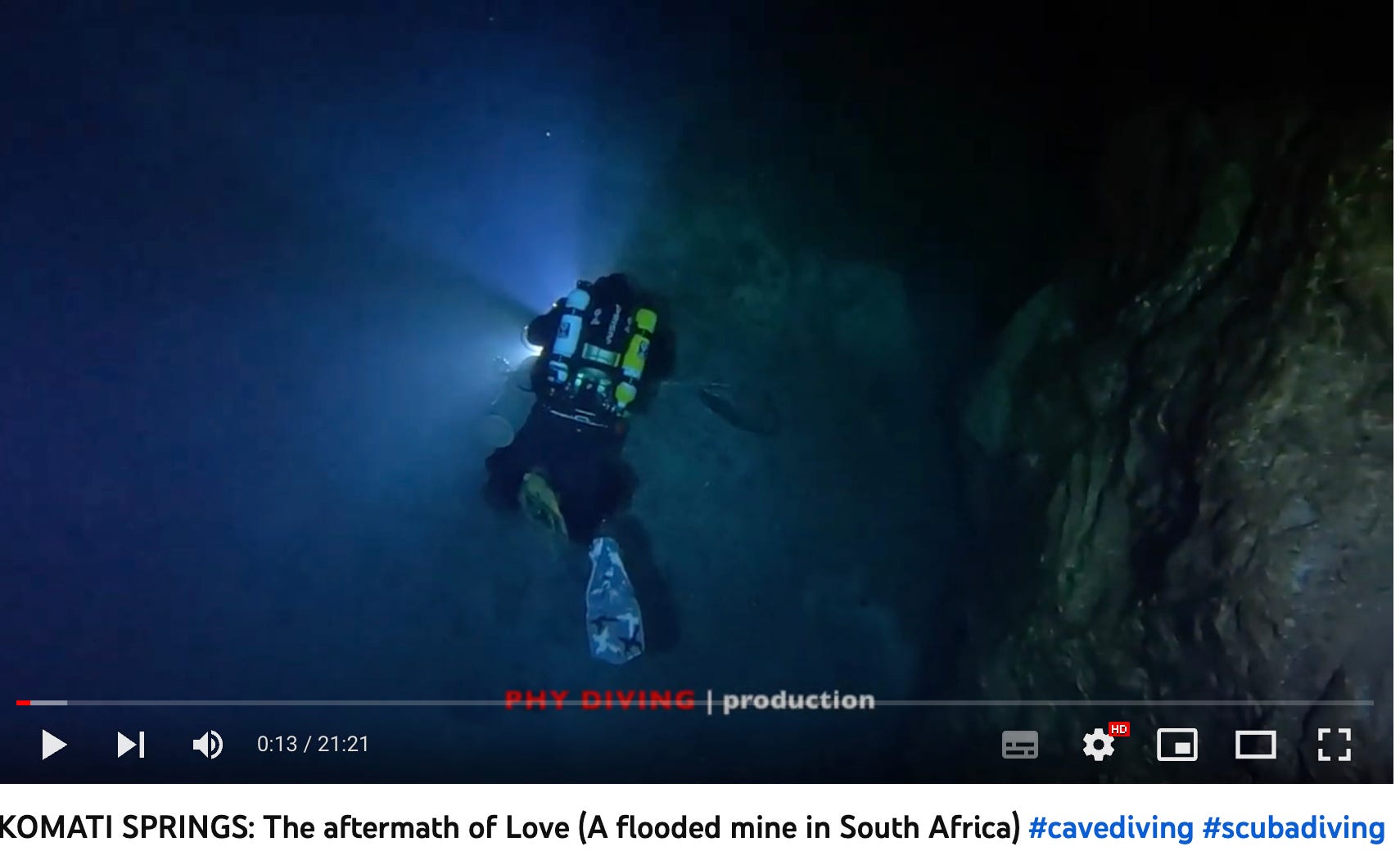

Andrea Murdock Alpini has written an article about a recent trip to dive in Komati Springs.

This is how he begins…

There was not even a star in the heavens tonight. The vault of the sky was obscured by clouds that, pushed by the northern winds, reached this flap of South Africa on the border with Swaziland.

Nature here was wild. Metre after metre, civilisation marked by the surrounding villages seemed to slowly disappear, swallowed by the primordial forest. It was a green wave merging everything together and defining the landscape as an infinite expanse of trees from which primaeval peaks emerged.

I was standing on a plateau at an altitude of 900m, where rocky outcroppings appeared low and desolate. They dotted the thick bush here and there. The highest mountain reached up to 1,400m, but it was not the altitude that characterised it, but rather its age.

I was told that the peak was 4.5 billion years old. “The Americans have the Grand Canyon, but it is nothing compared to our Old Mountain,” say the locals.

On the same trip, Alpini spent time with technical diving pioneer Don Shirley and his wife Andre, who own and run the dive centre at Komati Springs and wrote a sensitive, perceptive and beautifully composed article about Don and David Shaw, whose close friendship came to a tragic end on an ultra-deep body recovery dive in the Boesmansgat sink hole in South Africa’s Northern Cape in January 2005. David died and it was only via an astonishing display of strength, courage and perseverance that Don survived, although the recovery process was arduous.

Alpini’s piece on Don and Dave is entitled The Aftermath of Love and is published in the latest issue of InDepth here.

He also made a short video - click on the image to watch…

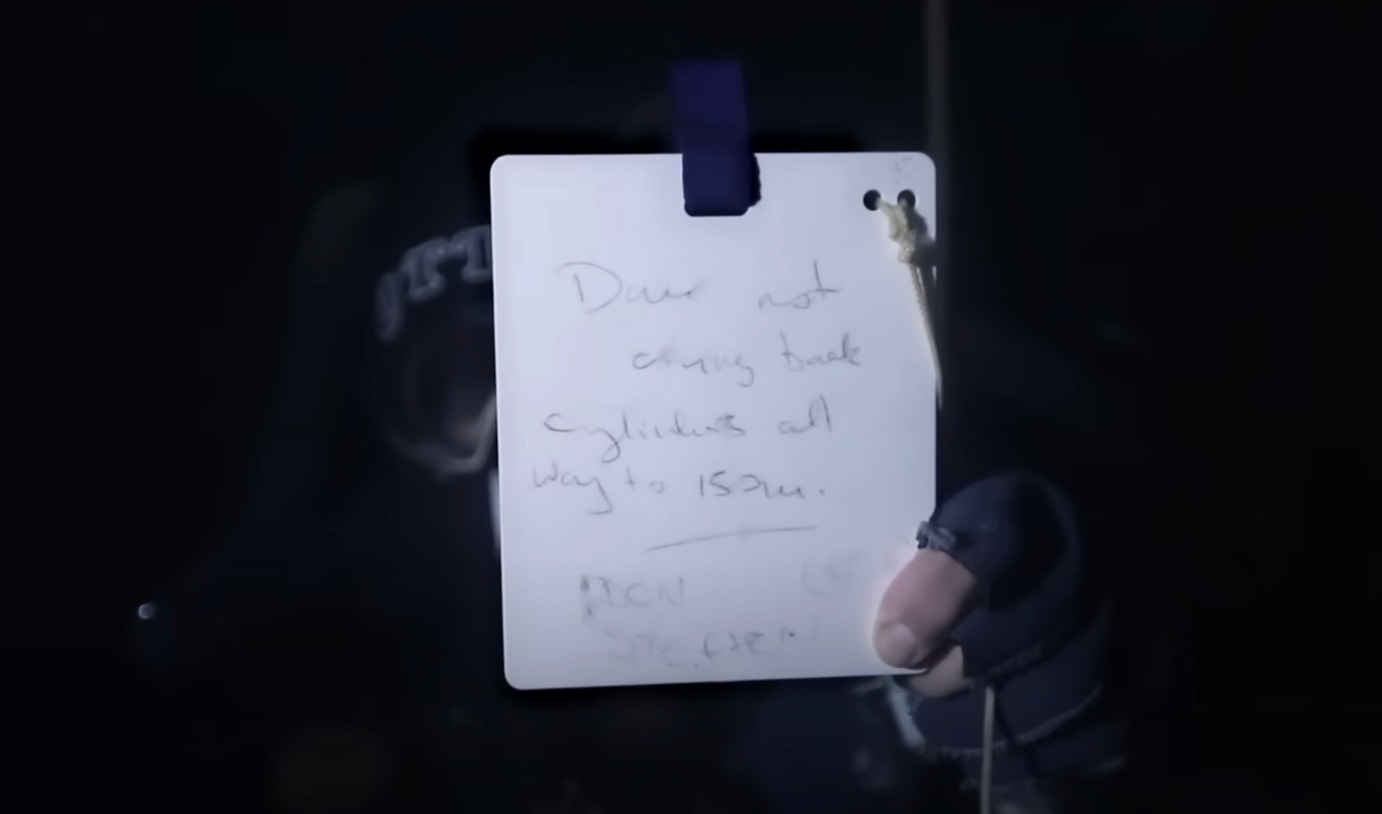

Their story is also the subject of a full-length feature movie called “Dave not coming back”, its title taken from what Don wrote on his dive slate when the deep safety divers joined him on his ascent.

This is also up on YouTube. Again, click on the link below.

The tragedy, the events leading up to it and the issues raised were also the subject of an excellent book called Raising the Dead by Phillip Finch, who did a beautiful job of handling a complex subject and creating an accessible real-life thriller without sacrificing accuracy.

This book is scuba diving’s Touching the Void and I highly recommend it.

There’s an edgy feel to this Scuba Conversational and the theme continues. The June issue of In Depth had plenty of excellent journalism and one of the best pieces was by Ashley Stewart, writing about a recent experimental mission conducted by a group of deep-diving cavers who call themselves the Wetmules.

The article is entitled

N=1. The Inside Story of the First-Ever Hydrogen CCR Dive

On March 11, a little more than three weeks after completing what is believed to be the first-ever rebreather dive with hydrogen as a diluent gas, Dr Richard “Harry” Harris convened the group of scientists and researchers who had spent years helping to plan the attempt.

He started with an apology. “All of you had the sense that you were party to this crime, either knowingly or suspecting that you were complicit in this criminal activity,” Harris, an Australian anesthesiologist and diver known for his role in the Tham Luang Cave rescue, told the group.

The apology came because the dive was dangerous—not just to Harris who was risking his life, but for the people supporting him who were risking a hit to their reputations and worried their friend may not return home. Harris and his team put it all on the line to develop a new technology to enable exploration at greater depths.

This is the cutting edge of sport diving - trying out new combinations of technology to enable divers to go deeper more safely, although the use of the word “safe” in this context is probably not appropriate. If you know anything about mixed gas, the next photograph, taken from the article, will make you shudder.

One thing that jumped out at me from this article was an echo from the early days of technical diving when convening a workshop/brains trust/gathering of interested parties from a variety of different fields of endeavour turned out to be a very effective way of solving difficult problems. Organising this sort of thing turned out to be something at which Michael Menduno - the Bob Geldof of technical diving - excelled, and here he is again in the 2020s putting people together.

In 2021, the year after Harris completed his deepest dive at the Pearse Resurgence, InDepth editor-in-chief Michael Menduno was taking a technical diving class and reading about the government looking at hydrogen as a diving gas again. “Technical divers should be at the table,” Menduno said he thought to himself at the time, “our divers are as good as anybody’s.” He called John Clarke, who had spent 27 years as scientific director of the U.S. Navy Experimental Diving Unit (NEDU), and discussed setting up a working group. Menduno’s next call was to Harris, who had shared his troubles with gas density at the Pearse Resurgence. Harris had also, separately, been thinking about hydrogen.

The so-called H2 working group met for the first time in May 2021 and included many of the top minds in diving medicine and research, including Clarke, NEDU’s David Doolette and Greg Murphy, research physiologist Susan Kayar who headed up the US Navy’s hydrogen research at the Naval Medical Research Institute (NAMRI), along with her former graduate student Andreas Fahlman. There was diving engineer Åke Larsson who had hydrogen diving experience, deep-diving legend Nuno Gomes, decompression engineer JP Imbert who had been involved in COMEX’s Hydrogen diving program, and anesthesiologist and diving physician Simon Mitchell. The group was later joined by Vince Ferris, a diving hardware specialist from the U.S. Navy, and explorer and engineer Dr. Bill Stone, founder of Stone Aerospace.

If you have read my Technically Speaking book, you will recognise several of these names from the 1990s and even earlier.

It’s all edge-of-the seat-stuff and author Ashley does a terrific job in getting the excitement across.

Ahead of the dive, Harris was preparing at home. The first thing Harris said he had to get his head around was—no surprise—the risk of explosion, and how to manage the gas to mitigate that risk. The potential source of explosion that Harry was most concerned with was static ignition within the CCR itself, plus other potential ignition sources like electronics, the solenoid, and adiabatic heating. Industrial literature—or “sober reading” as Harris calls it—suggested that the tiny amount of static necessary to initiate a spark to ignite hydrogen is .017 mJ, 400 times less than the smallest static spark you can feel with your fingertips and several hundred times less than required to ignite gasoline. “It ain’t much, in other words,” Harris said, noting that counterlung fabric rubbing against itself could generate just such a spark.

Gulp!

Closing the circle to bring this Scuba Conversational back to almost where we started, I was interested to see this piece in the Divers Alert Network blog by Tim Blömeke, who works with InDepth and Menduno and, you may recall, was the journalist I talked about last month who was providing good day-by-day reports from Rebreather Forum 4 in Malta.

Tim lives in Taipei - at the other end of the country from where we are in the deep south - and wrote a nice article about shore diving in Taiwan and the particular skills - and gear - required. As he says

Taiwan is one the places in the world where shore diving is the rule rather than the exception, and pandemic travel restrictions kicked things into high gear – over the past three years, you were either diving locally, or you weren’t diving. The particular challenges presented by local sites have made Taiwanese divers quite skilled at shore diving and led to a number of unique adaptations to equipment and practices.

It’s a good entertaining read.

We learned some of these lessons - especially the value of felt-soled boots, while we were doing our research for Dive into Taiwan, where some really nice dive sites were only accessible from shore. Here are a few of our pictures from those days. You don’t have to be a mountain goat - “steady as she goes” probably sums up the best strategy - but being a mountain goat helps, and if you have the option of a boat - take it!

Hi Tracy, thanks for noticing that. Yes, Geldof's activism and also his talent for assembling talent, for Live Aid, Band Aid and, most famously, bringing Pink Floyd back together for Live 8. :-)

My search wasn't exhaustive, and you may know something that I don't (hah! you know many, many things that I don't), but it appears to me that you are the first person in history to use the phrase "the Bob Geldof of technical diving". Well-played. Highly evocative. I'm guessing this was in reference to being an activist and firebrand, and not regarding penning such hits as "I Don't Like Mondays"